WAS THE 9/11 DECADE a disaster for individual freedom?

Within hours of the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, the noted libertarian activist John Perry Barlow warned that the night of totalitarianism was about to descend on American liberty.

"Control freaks will dine on this day for the rest of our lives," wrote Barlow, a founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation and a research fellow at Harvard Law School, in an e-mail to his followers. "Within a few hours, we will see beginning the most vigorous efforts to end what remains of freedom in America."

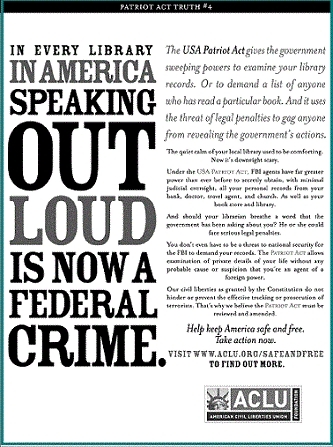

The ACLU's scare tactics notwithstanding, the Patriot Act did not make "speaking out loud" -- in libraries or anywhere else -- a federal crime. |

Barlow's voice was only the first in what would eventually be a deafening chorus denouncing the government's reaction to 9/11 as an assault on fundamental freedoms. George W. Bush, Jonathan Alter wrote in Newsweek, "thought 9/11 gave him license to act like a dictator." John Ashcroft, attorney general for the first three years of the Bush administration, was accused by the American Civil Liberties Union of displaying "open hostility to protecting civil liberties." Former Vice President Al Gore slammed the White House for using the war on terrorism "to consolidate its power and escape any accountability for its use."

Nearly every change in domestic national-security policy over the past decade, from airline no-fly lists to the data-mining of telephone records, was portrayed as another step down the slippery slope to a police state. Most reviled of all: the Patriot Act, passed by Congress six weeks after 9/11 and reauthorized several times since. Feverish critics characterized the law as the gateway to an American gulag. Under the Patriot Act, cried the ACLU, "the FBI could spy on a person because they don't like the books she reads or . . . the web sites she visits." To Ohio Representative Dennis Kucinich, debating the law on the House floor, it was "crystal clear" that the administration was determined "to abuse, attack, and outright deny the civil liberties of the people of this country in defiance of our constitution."

Some of this uproar was partisan, of course. That is why it was never directed at Barack Obama, even though he extended nearly all of Bush's national-security legacy.

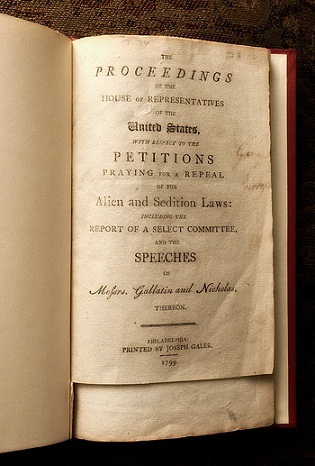

But in fairness, committed civil libertarians had reason to be uneasy. If the first casualty of war is truth, the second is often freedom. From the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 to the illegal harassment of political opponents during the Nixon administration, wartime governments have certainly been known to repress dissent and abuse individual rights. During the Civil War, the federal government rounded up thousands of civilians and shut down hundreds of newspapers because they publicly opposed the policies of the Lincoln administration. FDR ordered the internment of more than 100,000 loyal Japanese-Americans during World War II, though they were guilty of nothing but their ethnicity.

It was with historical precedents like these in mind that Wisconsin Senator Russell Feingold voted against the original Patriot Act – the only Senator to do so. Explaining his opposition, he quoted Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, who warned in 1963 that it is "under the pressing exigencies of crisis that there is the greatest temptation to dispense with fundamental constitutional guarantees."

The Alien and Sedition Acts were an odious assault on liberty and civil rights. But they were soon repealed, and have never been replicated. |

Yet 10 years later American freedom thrives. To be sure, obnoxious security measures are more common, especially in airports and other public spaces, but political debate, dissent, and activism are as robust as they have ever been. As the New York Times acknowledged this week, the domestic legal response to 9/11 "gave rise to civil liberties tremors, not earthquakes." The Patriot Act, for all the hyperventilating, amounted to little more than "tinkering at the margins" of existing law. By historical standards, "the contraction of domestic civil liberties in the last decade was minor."

Sincere the Feingolds and Barlows may have been, but they were wrong. American history doesn't prove that once the government's "control freaks" get a taste of expanded power, it is only a matter of time before the concentration-camp gates swing shut behind us. If anything, it proves the opposite.

Congress and the president may restrict political liberties during wartime or a crisis, but when the crisis eases liberty rebounds – and then some. The balance between security and freedom shifts back not to where it was, but to even greater liberty and expanded individual rights. Thus, after the Civil War ended, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments made the United States an even freer country than it had been before. Following World War II, FDR's internment of the Japanese was rescinded – and is now so reviled that no mainstream political figure would dream of defending or emulating it.

Americans are more jealous of their freedoms than libertarians sometimes realize. For nearly 150 years, civil liberties in this country have been on the upswing. Ten years after 9/11, they still are.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.