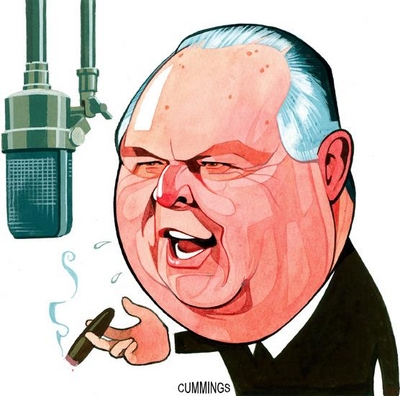

A LOT OF LIBERALS hate Rush Limbaugh -- or the caricature that they think of as Rush Limbaugh -- but even the most doctrinaire Bolshevik had to feel at least a twinge of sympathy when the nation's preeminent radio personality announced last week that he has gone almost completely deaf.

Or maybe not. Limbaugh has a strangely unhinging effect on some people. When Al Franken wrote a book about his fellow entertainer and commentator, he crudely titled it Rush Limbaugh Is a Big, Fat Idiot. The liberal columnist Carl Rowan once snarled that "the blood of America's race war victims will be on the hands and bloated bodies of Rush Limbaugh and Howard Stern." It is hard to say which was more grotesque -- the suggestion that Limbaugh is a racist or the comparison to a bottom-feeder like Stern. And there is even uglier stuff where those examples came from.

So maybe there are some hard-core left-wingers out there so steeped in ideological bile that word of Limbaugh's awful setback is cause for mockery or glee. But for tens of millions of ordinary Americans, the news that Rush can't hear anymore comes as a tragic shock.

The irony is almost Shakespearean: It is Limbaugh's ability to hear that has been the key to his success. Of course he is a great talker, and of course his mouth -- his ability to hold forth for three hours a day, five days a week -- is a powerful asset. But it is his ear that has made him a cultural phenomenon: His ear for the sentiments of Middle America, his ear for its patriotism and practical sense, his ear for what Main Street finds funny, or crazy, or inspiring. Lots of microphone jockeys have the gift of gab. Very few have the instinct for their audience -- for its convictions, its frustrations, its political judgment -- that Limbaugh does. That is the source of his tremendous acclaim.

"I approach my audience with enormous respect," Limbaugh wrote in a 1994 article for Policy Review, the journal of the Heritage Foundation. "These are the people whose most heartfelt convictions have been dismissed, scorned, and made fun of by the mainstream media. I do not make fun of them."

On the contrary: He gives voice to their thoughts.

"Despite claims from my detractors that my audience is comprised of mind-numbed robots, waiting for me to give them some sort of marching orders," he continued, "the fact is that I am merely enunciating opinions and analysis that support what they already know. Thousands of listeners have told me, on the air, in faxes, letters, and by computer e-mail, that I agree with them. Finally, they say, somebody in the media is saying out loud what they have believed all along."

In July, Limbaugh signed the biggest contract in radio history, a $285 million deal to continue broadcasting through 2009. If the free market is right about Limbaugh, there has never been a radio host with greater appeal. And that is because there has never been a radio host more in sync with the feelings and attitudes of his countrymen.

Limbaugh could never have earned such esteem if he were a racist and hate-peddler. Honest liberals admit as much.

In 1993, Washington Post columnist William Raspberry wrote a piece blasting Limbaugh for his "demagoguery ... his gay bashing, his racial putdowns." Like the Mississippi segregationists of his youth, Raspberry said, Limbaugh "is so good at . . . tossing the raw meat of bigotry to people. . . . Limbaugh is a bigot."

Eleven days later, Raspberry wrote a second column retracting the first.

"Rush, I'm sorry," he began. He confessed, to his great credit, that the earlier piece had been written in ignorance. "My opinions about [Limbaugh] had come largely from other people -- mostly friends who think Rush is a four-letter word. They are certain he is a bigot. Is he?"

Raspberry -- who by this point had listened to several hours of Limbaugh's shows and perused one of his books -- went on to answer his own question. Limbaugh might be "smart-alecky" and love "to rattle liberal cages," he might be "unrelenting in his assault on ... political correctness." But he was no more a bigot or hatemonger than Art Buchwald.

I have never met or spoken with Limbaugh, and I don't often get the chance to tune in to his program. But I can attest to his extraordinary reach and influence.

A few weeks before Bill Clinton's re-election in 1996 I wrote a column headlined "Four more years? Here are 40 reasons to say no." Shortly after noon on the day it appeared, my phone began ringing off the hook with queries about it. E-mail requests for the column began streaming in. I couldn't understand the explosion of interest -- until I learned that Rush had read the column over the air, raving about it to his 20 million listeners. When he mentioned that it could be found on The Boston Globe's web site, the digital tidal wave that ensued crashed the server -- but not before breaking the site's previous daily record for visits by more than 1 million. The switchboard operators, bless their patience, were deluged for days.

Over the next few weeks, so many people contacted the Globe to request the issue with my column that the Back Issues Dept. laid in an extra 1,000 copies -- and sold out of them all. It was the most-requested issue of the paper, I was told, since Larry Bird retired from the Celtics.

With the comical pomposity that is part of his shtick, Limbaugh often crows that he has "talent on loan from God." Now God has sent him a trial to go with the talent. May he come through it with his gifts and good humor intact.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --