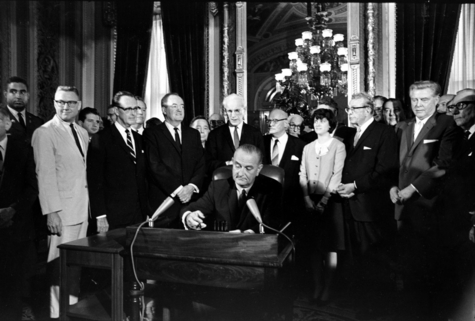

August 6, 1965: President Lyndon Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act into law, calling it "a triumph for freedom as huge as any victory that has ever been won on any battlefield." |

LIKE EVERYTHING else in our polarized age, reaction to the Supreme Court's 5-4 ruling in Shelby County v. Holder divided sharply along political lines. The court held Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act unconstitutional, effectively lifting the burden on certain states to get federal approval before making any change to their election procedures. Predictably, conservatives and liberals clashed over whether the majority opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts got the constitutional law right.

But I was struck less by the legal arguments than by the angry denial on the left, especially among minorities, that the ingrained racial disenfranchisement the Voting Rights Act was enacted to eradicate is dead and buried. The defeat of Jim Crow is one of the great progressive triumphs of American history. But to hear the outraged critics, you'd think the court had just thrown the door open to a revival of poll taxes and literacy tests. Worse, you'd think white Americans were eager to revive them.

It saddened me to hear an emotional John Lewis, who was on the front lines of the civil rights struggle in the 1960s and is now a congressman from Georgia, blast the court for plunging "a dagger" into black political emancipation. "Voting rights have been given in this country and they have been taken away," he said. The gains made by freed slaves during Reconstruction "were erased in a few short years." Lewis is sure it could happen again.

Other civil-rights advocates strike the same foreboding tone. Harvard law professor Charles Ogletree insists that black voting rights are "being threatened at a level we haven't witnessed ... since before the Voting Rights Act was passed." A spokeswoman for MALDEF, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, says the court's ruling "tries to disenfranchise Latinos and minorities from voting." The NAACP's Sherrilyn Ifill expresses alarm at a decision that "leaves virtually unprotected minority voters in communities all over this country.... This is a real threat."

I realize that part of this is posturing for effect by those with a vested interest in provoking racial anxieties. But I don't doubt that much of the fear and anger is genuinely felt, kept alive by communal memories of slavery and segregation that still exert a powerful psychological toll. To most Americans it may be an obvious and happy fact that the evils of Jim Crow are gone for good. For too many blacks, however, the chains of remembrance make it impossible to believe that the old racist impulses aren't still smoldering, ever ready to ignite.

During a 1963 voter registration campaign known as Freedom Day, police arrest activists for holding placards urging black Americans to register at the county courthouse in Selma, Ala. |

Our capacity to remember, and to draw meaning from our memories, is invaluable to our humanity. I was raised in a Jewish tradition that raises remembrance to the level of religious obligation – "Remember what Amalek did to you along the way when you came out from Egypt" is one such injunction – and among a community of Holocaust survivors for whom "Never Forget" became almost an 11th Commandment.

But there is such a thing as remembering too much, of being so focused on the horrors of the past that present realities become permanently distorted. A child who lived through the Depression becomes a lifelong hoarder of string and scraps, incapable of accepting that the abundance she knows today won't be gone tomorrow. The same thing can happen to communities, groups, and nations. Collective remembrance can be ennobling and enriching. But it can also be debilitating.

Many American Jews, for example, are so indelibly shaped by historical memories of Christian anti-Semitism that they find it impossible not to be suspicious of the sincere philo-Semitism so common among evangelical Christians today.

Or consider a more global example: the impact of collective memory on modern European defense policy. Scarred by two horrendous world wars, much of Europe came to the conviction that military might and nationalist feeling are fundamentally illegitimate, and that security is best ensured through treaties, multilateral organizations, and the minimizing of sovereignty. The result, time and again, has been a rift between US administrations that believe in peace through strength and a European establishment that embraces appeasement as the safest response to aggression.

It is true, as Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in her passionate Shelby County dissent, that "what's past is prologue." But what it is prologue to is not always more of the same. Sometimes the evils of the past really do lead to heartfelt — and permanent — progress. Even if some people, paralyzed by memory, cannot bring themselves to believe it.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe. His website is www.JeffJacoby.com).

-- ## --