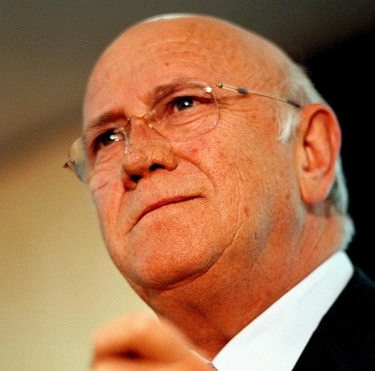

F. W. de Klerk's role in South African history will be recalled with astonishment and admiration. |

"I WOULD LIKE to be remembered positively," Frederik W. de Klerk once said, "as one of the leaders who at the right time did the right thing." He needn't worry.

Last week, de Klerk resigned from Parliament and closed his career in South African politics, mostly for reasons having to do with the internal politics of his sputtering National Party. But however mundane the details of his leaving, his hour on the stage of history will be recalled with astonishment and admiration.

For de Klerk is the man who toppled the pillars that upheld apartheid. He rose courageously above the racist apartheid ideology in which he had been reared. Rose above the legacy of his family, one of South Africa's great National Party clans. Rose, even, above his political ambitions: In shattering apartheid, he knowingly shattered his own grip on power.

President Nelson Mandela remarked that he hoped South Africans wouldn't forget "the role de Klerk played in effecting a smooth transition from our painful past to the dispensation South Africa enjoys today." That was a rather bloodless send-off for the man who did more than anyone else to make possible Mandela's rise to power.

Which is not to take anything away from Mandela. A generation behind bars would have encrusted many men in bitterness. They turned Mandela instead into a peacemaker, one who leads his country with a seemliness Africa's other leaders would do well to emulate.

But it was not Mandela who single-handedly forced his country's white power structure to forfeit the racist legal system it had spent 40 years entrenching. It was de Klerk.

In the 1980s, pundits sorted Afrikaner politicians into two camps: the "verligte" (enlightened) and the "verkrampte" (reactionary). When de Klerk became president in September 1989, it wasn't clear which persuasion he belonged to. He had supported the tiny reforms instituted by his predecessor, P. W. Botha. But he had also nearly lost his seat to a hard-line opponent of reform, hanging on by just 1,500 votes.

Within days, de Klerk placed himself squarely among the "verligte." A week after taking office, he announced that protest rallies, banned under the nation's "state of emergency," would be permitted. In Cape Town and Johannesburg, 40,000 demonstrators promptly put his words to the test. A few weeks later, the new president ordered eight prominent black dissidents, including Walter Sisulu of the banned African National Congress, released from prison. In Soweto, 70,000 people rallied unmolested in celebration.

South Africans were stunned. But de Klerk had just begun. "Our goal," he said in December, "is to ensure that all the citizens of this country will become first-class citizen." And he added: "Time is of the essence."

On Feb. 2, 1990, addressing Parliament on its opening day, he announced that Mandela would be released and that the ANC would be unbanned. On Feb. 11, Mandela walked free from his prison cell. In June, emergency regulations were lifted in all but one province. Press controls were eased. Talks with the ANC were opened. The beaches were desegregated. The Separate Amenities Act was repealed.

De Klerk's reforms, so unexpected and swift, "have taken my breath away," marveled Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

Then, in February 1991, de Klerk blew up the very cornerstones of apartheid. He told parliament that the Group Areas Act forbidding integrated communities would be abolished. So would the Population Registration Act, which classified South Africans by race. And the Land Acts that reserved 87 percent of the country's land to whites. Segregationists, in a fury, stalked from the chamber.

De Klerk pressed on. He appointed nonwhites to his Cabinet. He named Harry Schwarz, a longtime antiapartheid activist and a leading member of the opposition party, ambassador to the United States. And then he staked everything on a vote — a whites-only referendum asking, in effect, whether apartheid and all its privileges should be dumped.

Crafting great reforms, then letting the people judge: This was the gamble Mikhail Gorbachev never dared to take, the gamble Charles de Gaulle took and lost. De Klerk won. Nearly 69 percent of South African whites voted to continue on the road to equality.

South African President F. W. de Klerk in 1990 with a newly-freed Nelson Mandela, the charismatic hero of the anti-apartheid movement. |

It was a historic victory, and it ensured a historic loss. De Klerk knew his presidency would end after the next election. He didn't falter. In October 1993, he won, with Mandela, the Nobel Peace Prize. Six months later, he shared a greater honor: running in South Africa's first free election — an election he, above all others, had brought about.

Other African leaders — Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah — led their people out from under the domination of alien powers. De Klerk's achievement was vastly more difficult. He led his nation out from under the domination of an alien idea — the idea of minority white rule in a majority black nation. For Kenyatta and the others, victory meant power. For de Klerk, it meant the loss of power — as he knew it would.

It is easy to underestimate de Klerk's role in history. In retrospect it seems clear that apartheid was doomed. But nothing was clear when he came to power. He could have led South Africa into deeper repression, into bloodshed, even into civil war. Instead, against his self-interest, he set a course for democracy and the rule of law. He is indeed one of those leaders "who at the right time did the right thing." He may well be the greatest African statesman of the 20th century.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.