Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Ind., last week unveiled a sweeping proposal to devote tens of billions of dollars and expanded federal powers to, in his words, the "dismantling" of America's "racist structures and systems."

Buttigieg calls his proposal the "Douglass Plan," in honor of the great 19th-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass. In its vast scope and ambition, he says, it would be like the Marshall Plan that helped rebuild Europe after World War II. But the Marshall Plan was a straightforward economic recovery project compared to the social transformation Buttigieg has in mind.

Under the "Douglass Plan," a Buttigieg administration would pour vast sums of money into black institutions, health programs, and schools. It would expand racial preferences for government contracting, and spend more money to "diversify the teaching profession." It would eliminate "broken windows" policing, which focuses on curbing low-level crimes to discourage more serious offenses. It would also abolish the death penalty, cut the prison population in half, provide student grants and Medicaid benefits to prison inmates, and make it harder for criminals released on probation to be sent back for "small violations." And it would make the promotion of black history a federal priority.

All of this, says Buttigieg, would be in addition to — not instead of — a system of reparations for the descendants of slaves. And the "Douglass Plan" doesn't stop with issues that are explicitly connected to race. It also includes elimination of the Electoral College.

And statehood for Washington, D.C.

And a constitutional amendment overturning Citizens United.

And public financing of election campaigns.

And an end to political gerrymandering of legislative districts.

And a "Lead Paint Mitigation Fund."

And more money for disaster preparedness and relief.

And a "Community Homestead" program to purchase abandoned urban properties and turn them over at no cost to "eligible residents" who promise to rehabilitate them.

And a $15-per-hour federal minimum wage.

In other words, Buttigieg's "Douglass Plan" comprises not only a massive program of racial preferences, affirmative action, and public spending on the basis of color, but also hefty chunks of the progressive wish-list. In that respect, it is similar to the Green New Deal, which — as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's chief of staff has said — should not be thought of as "a climate thing" but as "a how-do-you-change-the-entire-economy thing."

According to opinion polls, Buttigieg has so far failed to gain any traction with black voters, and has been criticized for his handling of race-related issues in his home town. Will the "Douglass Plan" change that? I can't imagine anyone being inspired by a proposal that describes America as profoundly racist, while suggesting that the cure lies in focusing even more obsessively on people's race. But then, I'm not a Democratic Party primary voter, so Buttigieg's pitch isn't targeted at me.

Apparently it also isn't targeted at anyone who knows anything about the man for whom it is named.

Frederick Douglass would have been appalled by the "Douglass Plan." A passionate and active abolitionist before the Civil War, he was no less ardent in defending the rights of black freedmen after slavery was abolished. He never wavered in demanding the liberty and equal rights to which black Americans were entitled, and he spoke angrily and loudly against those who schemed to prevent the former slaves from improving their economic condition.

Frederick Douglass, born into slavery, became a renowned abolitionist, orator, journalist, and public official |

But he was always contemptuous of the idea that blacks lacked the intellectual or moral capacity to stand on their own two feet. Secure their right to vote, to legal equality, to work without being swindled, and African Americans would thrive, he maintained. "What I ask for the Negro is not benevolence, not pity, not sympathy, but simply justice ," Douglass said. Blacks did not need to be patronized or condescended to. The best thing government could do was ensure that they were not discriminated against; but no one should imagine that they could not succeed unless the government discriminated in their favor.

"I utterly deny that we are originally, or naturally, or practically, or in any way, or in any important sense, inferior to anybody on this globe," declared Douglass in Boston on January 26, 1865, in a speech to the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society.

Everybody has asked the question, and they learned to ask it early of the abolitionists, "What shall we do with the Negro?" I have had but one answer from the beginning. Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us! If the apples will not remain on the tree of their own strength, if they are worm-eaten at the core, if they are early ripe and disposed to fall, let them fall! I am not for tying or fastening them on the tree in any way, except by nature's plan, and if they will not stay there, let them fall. And if the Negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone! If you see him on his way to school, let him alone, don't disturb him! If you see him going to the dinner table at a hotel, let him go! If you see him going to the ballot-box, let him alone, don't disturb him! If you see him going into a work-shop, just let him alone – your interference is doing him a positive injury. . . . Let him fall if he cannot stand alone!

Douglass was speaking as the Thirteenth Amendment was on the cusp of adoption by Congress, and it would be another 11 months before the language abolishing slavery was ratified and added to the Constitution. But Douglass had no doubts about the innate aptitude of the black American. "If you will only untie his hands, and give him a chance," the great man insisted, "I think he will live."

He never stopped thinking so. In one of his most popular speeches, "Self-Made Men," Douglass years later asserted his faith in the power of diligence and hard work to raise up even men and women who had previously been trapped in slavery.

"Personal independence is a virtue and it is the soul out of which comes the sturdiest manhood," he declared as a general principle. "But there can be no independence without a large share of self-dependence, and this virtue cannot be bestowed. It must be developed from within."

That applied to black men and women no less than any others:

I have been asked "How will this theory affect the Negro?" and "What shall be done in his case?" My general answer is "Give the Negro fair play and let him alone. If he lives, well. If he dies, equally well. If he cannot stand up, let him fall down."

Douglass acknowledged the seeming unfairness of expecting former slaves, who had started out "from nothing and with nothing," to be held to the same rules as those who had "start[ed] with the advantage of a thousand years behind them." But he refused to budge on the point: Give the freedmen an equal chance to compete, and they would succeed.

The nearest approach to justice to the Negro for the past is to do him justice in the present . Throw open to him the doors of the schools, the factories, the workshops, and of all mechanical industries. For his own welfare, give him a chance to do whatever he can do well. If he fails then, let him fail! I can, however, assure you that he will not fail. Already has he proven it. As a soldier he proved it. He has since proved it by industry and sobriety and by the acquisition of knowledge and property. . . . In a thousand instances has he verified my theory of self-made men. He well performed the task of making bricks without straw: now give him straw. Give him all the facilities for honest and successful livelihood, and in all honorable avocations receive him as a man among men.

Whatever black Americans may have to contend with today, it pales in comparison with the cruelty, betrayal, and repression that followed the collapse of Reconstruction and the resegregation of the South. If there was wisdom in Douglass's words 150 years ago — "Do nothing with us!" — how much more so is there wisdom in them today, when African Americans are incomparably better-equipped for success than they were in the 1860s and 1870s. Affirmative action, racial preferences, minority set-asides, benefits for prison inmates, reparations for slavery, billions in public funding for black institutions — Douglass would have wanted nothing to do with such paternalism, or with the endless insistence that America is incorrigibly and permanently steeped in anti-black bigotry.

Buttigieg's "Douglass Plan" makes this claim: "After the accumulated weight of slavery and Jim Crow, America cannot simply replace centuries of racism with non-racist policy; it must intentionally mitigate the gaps that those centuries of policy created." Perhaps Buttigieg really believes that; perhaps he is merely saying it for political purposes. Either way, it flies in the face of what Douglass believed and said.

Buttigieg is free, of course, to reject the judgment and insight of one of the greatest statesmen, advocates, and thinkers in African American history. But if he is going to campaign for president on a plan that Frederick Douglass would have spurned, he should have the decency not to call it the "Douglass Plan."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

How to throw New Hampshire out of work

The federal minimum wage is $7.25 per hour, but Democrats have been clamoring for a while to more than double it to $15 per hour. Nearly all the Democratic presidential candidates have endorsed a $15 minimum wage, and in several cities (Seattle, Austin, New York), a $15 minimum is already mandated by law.

When government raises the lowest hourly wage at which a worker may lawfully be employed, does that help or hurt those at the bottom of the economic ladder?

"The issue has been fought over for decades," I wrote last year.

Reality repeatedly renders the same verdict: Artificially hiking minimum wages makes it harder to employ unskilled workers. Raising the cost of labor invariably prices some marginal laborers out of the job market. Advocates of higher minimums may wish to ensure a "living wage" for the working poor. Yet the result is that fewer poor people get work.

This really shouldn't be a liberal-vs.-conservative or Democrat-vs.-Republican issue. One of the most elementary facts of economics is that raising prices reduces demand. It's true of widgets, whiskey, and washing machines, and it is no less true of workers. The New York Times put it succinctly in a 1988 editorial headlined "The Minimum Wage Illusion :

The question is whether legislating a higher minimum would improve life for the working poor.

It definitely would — for those who still had work. But by raising the cost of labor, a higher minimum would cost other working poor people their jobs.

Two studies in 2017 examined the impact of recent minimum-wage increases in Seattle and San Francisco. In the Seattle study , economists commissioned by the city found that the increase caused a decline in the employment of low-wage workers, just as opponents had predicted. Some workers lost their jobs, while many who remained employed had to accept a cutback in hours. When the gain from higher hourly wages was set against the loss of jobs and hours, the bottom line was stark: "The minimum wage ordinance lowered low-wage employees' earnings by an average of $125 per month."

The other 2017 study, conducted by Harvard Business School scholars, analyzed the effect of minimum wage hikes on San Francisco-area restaurants. Result: For every $1 increase in the mandatory minimum wage, there was a 14 percent increase in the likelihood that a median-rated restaurant would go out of business.

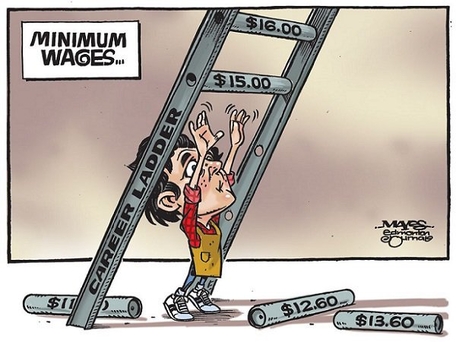

All of this is in keeping with basic economic teaching. Minimum-wage laws can set the lowest rung on the pay ladder, but they can't ensure that every employee will be able to reach it. In practice, minimum wage increases tell low-skilled workers: If you can't find an employer willing to pay you more money, you may not work. That isn't benevolent, it's spiteful. And it's why raising the minimum wage almost always prices some vulnerable workers out of the labor market.

Last week, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office issued a report analyzing the effects of raising the federal minimum wage. It concluded, as objective economists always do, that while some workers could expect a raise, others would lose their jobs.

According to CBO's median estimate, if the minimum wage were pushed to $15 an hour, 1.3 million workers who would otherwise be employed would be jobless. As the Concord, N.H.-based Josiah Bartlett Center points out, 1.3 million people is equal to the entire population of New Hampshire. And that's the median estimate: Under the CBO's worst-case scenario, job losses caused by a $15 minimum would be far higher — 3.7 million people would be thrown out of work. That's more than the total population of Connecticut.

Liberal legislators, journalists, and activists commonly avoid the real-world impact of minimum-wage increases, or they hide it behind uplifting rhetoric about compassion and social justice. They challenge anyone who opposes a higher minimum wage to try living for a week on the existing one. Wouldn't you find it excruciating, they say to critics, if you had to make do with $7.25 an hour?

No doubt they would. But having to make do with $0 an hour would be more excruciating by far — and $0 is the wage earned by people who are unemployed because a hike in the minimum wage drove their employer to lay them off, or prevented them from being hired in the first place.

Politicians cannot cure poverty by raising the cost of entry-level employment any more than they can do so by waving a magic wand. After all, if aiding the needy were as easy as setting a compulsory minimum wage, why not set it at $20 an hour — or $120 an hour — and really help them out?

The effects of supply and demand are not optional. They weren't enacted by lawmakers and lawmakers can't override them. Bromides about giving a raise to the working poor may give legislators and advocates a warm glow. But there is nothing soothing about losing your job because Congress makes you too expensive to hire.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter