The defeat of Proposition 16 was a defeat for discrimination

One of the most gratifying and wholesome results of last week's election was the defeat in California of Proposition 16. That ballot measure would have stripped from the state constitution the provision that makes it illegal for the government to "discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin." That language was added to the California constitution in 1996, and race-obsessed progressives had been fulminating against it ever since. This year, the overwhelmingly Democratic legislature placed a repeal proposition on the ballot, then embarked on a full-court press to make sure it passed.

"The full weight of California's political establishment — including a Democratic governor, a long list of elected officeholders, deep-pocketed donors, business leaders, and even several professional sports franchises — are lining up behind Proposition 16," the San Jose Mercury News reported in September. Leftists and Democratic officials spun Proposition 16 not as a measure to legalize racial discrimination, which would have been an accurate description, but as merely an anodyne adjustment that — to quote the language that appeared on the ballot — "allows diversity as a factor in public employment, education, and contracting decisions."

Money poured into the Yes-on-16 campaign. It raised more than $19 million and spent it all to advertise heavily for the restoration of racial preferences by the state. Much of those funds went to TV commercials in which opponents of Prop. 16 were described as "those who have always opposed equality" — a libel that was accompanied by video of white nationalists rallying in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017. The libels were freely flung about on social media, too. Democratic politicians like David Chiu, a member of the California Assembly, smeared the anti-16 campaign — the most visible leaders of which were Asian — as "tied to white supremacy" and "to the most insidious & hateful forces in the US."

Opponents of the ballot initiative, meanwhile, raised only $1.3 million, and were barely able to respond to the flood of attacks on their character and motivations. But while they lacked the deep pockets of the pro-discrimination, pro-preferences contingent, they had the deep sympathy of California voters, including millions who were neither white nor male. Those voters instinctively recoiled from the idea that government should be allowed to discriminate on the basis of race, sex, and color.

It was a classic David-and-Goliath contest. On Election Day, despite being massively outspent, the No campaign prevailed handily. Proposition 16 went down to defeat, 56.5 to 43.5 — a 13-point margin of victory for the opponents of official discrimination.

Have Prop. 16's advocates accepted their defeat gracefully, and acknowledged that they were badly out of touch with California voters? Of course not. They insist that they lost not because identity politics and racial discrimination are unpopular, but because the voters didn't understand what they were voting on.

"The ballot language itself was confusing," said Oakland's Eva Paterson, a co-chair of the Yes-on-16 campaign. "We just weren't able to get through to voters. . . . People who didn't understand the purpose of Prop. 16 didn't get it." The same lame claim was offered by Michele Siqueiros, another advocate of racial and ethnic preferences. "I think voter confusion was our biggest uphill battle," she said. "We know that when folks read the ballot description that they were simply confused by it."

What a pathetic excuse for failure. The campaign to re-legalize government discrimination sought to exploit voter confusion, by portraying the purpose of Proposition 16 as an initiative in support of inclusiveness, diversity, equity, balance, and racial justice — and by suggesting that anyone opposed to the ballot measure must be a hate-filled bigot. Rarely did advocates respond honestly to the profound moral argument against sorting people by race — the cause to which Martin Luther King Jr. devoted his life. Virtually every lever of power and every influential voice in the state was deployed in support of Proposition 16. It was backed by Governor Gavin Newsom and Senator Kamala Harris, by US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, by the Los Angeles Times and the San Diego Union-Chronicle, and by hundreds of local governments, labor unions, corporations, and activist groups.

The pro-Prop. 16 drumbeat was incessant. It was depicted relentlessly as a constitutional change that no one could in good faith oppose. Everyone who was anyone was for it.

But voters saw through the propaganda and voted no.

Not because they were confused, but because they weren't.

In a memo last week, Gail Heriot — a law professor at the University of San Diego and a member of the US Commission on Civil Rights — demolished the claim that confusion sank Proposition 16, or that the Election Day outcome was in any way a fluke.

"The polls have been consistent for decades," Heriot wrote. "Whenever the issue is stated fairly and clearly, opposition to race and sex preferences is overwhelming."

At least four times since 2003, she noted, Gallup has asked respondents whether they believe college students should be admitted solely on the basis of merit, or whether their racial and ethnic identity should be taken into consideration. The findings have been unequivocal:

The number of respondents choosing "solely on merit" is always at least twice as great as the number choosing "help promote diversity." In 2016, it was 70% for "solely on merit" vs. 26% for considering racial or ethnic background.

A Pew Research poll in 2019 focused on affirmative action in employment. Pew asked respondents to choose between two choices:

"When it comes to decisions about hiring and promotions, companies and organizations should —

. . . Only take qualifications into account, even if it results in less diversity.

Or . . . also take race and ethnicity into account in order to increase diversity."

Again, the results were unequivocal: 3 out of 4 respondents said employers should "only take qualifications into account." Just 1 in 4 favored preferences for race and ethnicity.

To be clear, respondents by a lopsided margin support diversity in the workplace. But they don't believe it should be achieved by discriminating for or against job applicants on the basis of race or ethnicity.

"I can personally attest to the fact that many left-of-center Californians opposed Prop. 16," wrote Heriot. "Some helped out the campaign in large or small ways. I suspect that anyone who goes through our list of donors will find quite a few registered Democrats among them. They weren't confused about Prop 16. They understood it all too well."

Among mainstream Americans, public opinion on the question of racial preferences has changed very little over time. The MLK standard — judge people not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character — continues to exert a powerful moral pull. California elites and political insiders were gung-ho for reviving racial discrimination by the state, but at the grassroots it remains a deeply unpopular position. As it should.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Tax-and-spend myths and facts

Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, is a walking compendium of federal tax and spending data, much of which he compiles each year into a big "Book of Charts." The most recent annual edition was released last month, and its contents are a budget geek's nirvana. They lay out a pretty incontestable picture of relentlessly soaring spending, steadily increasing national debt, and budget deficits (to coin a phrase) as far as the eye can see. They also bust a number of popular myths about the causes of Washington's profligacy.

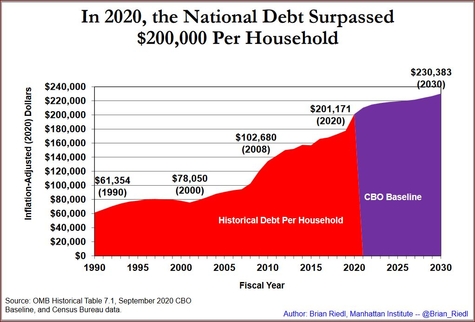

As of 2020, one of Riedl's charts shows, America's national debt surpassed $200,000 per household. Another chart makes clear that it is government spending, not lower revenues, that is driving the long-term deficit. Still another confirms that the lion's share of that spending goes to Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and interest on the national debt. Government outlays on antipoverty programs are almost entirely unaffected by which party is in power: It has inexorably risen under Republicans and Democrats alike — from just one-half of 1% of GDP in the early 1960s to 4% of GDP today.

Indeed, antipoverty spending has continued to skyrocket at a far faster rate than the population of people with incomes below the poverty line. From 2001 through 2019, the number of Americans living in poverty rose by about 1 million, or 3%. During the same period, the SNAP (food stamp) caseload increased by 18 million, or 106%.

Americans are up to their nostrils in government debt — and there is no end in sight. |

Many of Riedl's data compilations dismantle common talking points, as he explains in a related essay for National Review. It is untrue, for instance, that surging defense spending — the costs of the much-decried "trillion-dollar wars" — are largely responsible for the government's reliance on deficit spending. On the contrary,

the general trend has been declining defense spending as a share of the economy. Defense spending averaged 5.7% of GDP in the 1970s and 1980s, and was still 4.6% of GDP as late as 2010. It has since fallen to 3.2% of GDP and is projected to continue falling to 2.9 percent in a decade – matching its smallest share of the economy since the 1930s, and not far above the 2% of GDP target for our NATO allies. Since 2017, defense has comprised a record low of 15% of federal spending.

Another popular myth is that America has been drowning in red ink because of the 2017 Trump tax cuts. Fact-check: False.

"Even if the tax cuts are renewed," observes Riedl, "their $200 billion annual cost cannot explain more than a fraction of the budget deficit's [projected] expansion from $600 billion to $2 trillion between 2016 and 2030." By far the largest driver of the yearly budget deficit is the chunk of money annually withdrawn from the Treasury to pay for Social Security and Medicare benefits. Over the same 14-year period, as the Baby Boom generation retires, that chunk of money is expected to rise from $350 billion to $1.5 trillion.

More than any single government program, it is Social Security that is crushing the federal budget under an unsustainable debt load. "Over the next 30 years, the Social Security system will collect $52 trillion in payroll taxes and other . . . revenues and spend $74 trillion on benefits," Riedl writes. "The resulting $22 trillion deficit must be financed by outside revenues or borrowing." A $22 trillion shortfall for Social Security alone — that, right there, is the budget crisis in a nutshell. The crisis was in view long before the pandemic came along, and, absent a radical change in policy, it will remain a threat long after the coronavirus is behind us.

Soaking the rich cannot eliminate that threat. As yet another of Riedl's charts shows, even if Congress could impose a 100% tax rate on small businesses and upper-income households, it wouldn't raise nearly enough revenue to balance the budget. Add to the mix the progressive fantasy programs that Joe Biden endorsed in his presidential campaign — such as expanding Obamacare, reducing Medicare eligibility to 60, and a new economic stimulus package — and the budget would be even more lopsidedly imbalanced.

As a presidential candidate, Barack Obama condemned George W. Bush for "driving up our national debt from $5 trillion . . . [to] over $9 trillion." Such a sea of red ink was "irresponsible" and "unpatriotic," Obama said, promising that as president he would shrink it.

But if Bush's fiscal record had been "irresponsible," Obama's was off the charts. On his watch, annual budget deficits surged past $1 trillion. The national debt streaked upward, reaching nearly $20 trillion by the time he left office. Entitlements metastasized, consuming two-thirds of the federal government's outlays.

Yet today, with federal outlays and the national debt more out of control than ever, no one seems to care. Certainly not President Trump, though he disparaged the growth in debt when Obama was president and claimed he would have no trouble eliminating the "U.S. Debt Deficit" [sic] if he were president. Not Congress, which was setting new spending records even before the coronavirus outbreak. And definitely not voters, who worry much less about federal spending and the deficit than they used to.

So the madness persists. Through their government, Americans are up to their nostrils in accounts payable, yet all the political class wants to talk about is how much more money the government can spend. Our most pressing domestic issue isn't health care or housing or abortion; it is the colossal national debt that is slowly strangling America's future. We can avert our eyes and pretend not to see what lies ahead. But whether we look or not, it's coming.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, 1948-2020

"I recently celebrated my 72nd birthday," wrote Jonathan Sacks in The Spectator earlier this year. "Nothing special about that except for a sense of sheer improbability, having grown up with The Who singing 'Hope I die before I get old', one of the defining lines of the 1960s."

Like virtually everything written by Sacks — the former chief rabbi of the United Kingdom, life peer in Parliament, prolific best-selling author, and renowned public intellectual — the Spectator essay was erudite, eloquent, and elevating. It was also, as it turns out, sadly ironic. After beating back cancer in his 30s and his 50s, Sacks was diagnosed for a third time with the disease. He died two days ago, on Shabbat morning. There will be no 73rd birthday.

Sacks was a towering figure in the English-speaking Jewish world. He was an uncommonly gifted writer, an engaging speaker, and an inspiring teacher. His scholarly range was vast, yet he addressed his work to mainstream readers. He was a strictly observant Orthodox Jew, yet he reached an enormous non-Jewish audience. He was equally at home discussing ancient Torah scholarship or contemporary Western philosophy, and listeners hung on his words whether they were delivered to students in a yeshiva, to a BBC Radio audience, or to fellow members of the House of Lords.

Unlike other highly influential and admired Orthodox rabbis of recent decades, such as the last Lubavitcher Rebbe or Boston's Joseph Ber Soloveitchik, Jonathan Sacks was neither the scion of a rabbinic family nor a prodigy of Jewish learning from childhood. He grew up in a traditionally Jewish family, writes Israeli journalist Anshel Pfeffer, but for the first 20 years of his life — "going from his Church of England primary school to Christ's College high school and then Gonville & Caius College at Cambridge" — he had no formal Jewish education:

It would be the Six-Day War that changed everything. At 19, gathered together with other students in Cambridge's synagogue, he prayed for Israel's deliverance from a feared second Holocaust. The experience, he said, "planted a seed in my mind that didn't go away," and opened up "a burden of responsibility" to the Jewish nation.

He would spend the next decade studying and lecturing on moral philosophy before he finally joined the rabbinate. But his ascent in his belated vocation was meteoric. His sparkling oratory, natural charisma, and the originality of his sermons and books, fusing Jewish canonical texts with a wide range of Western thought, made him just the kind intellectual and spiritual rock star that Britain's fusty and hidebound Orthodox mainstream United Synagogue sorely needed to raise its stature.

For my family as for countless others, the words of Rabbi Sacks have long been a regular source of Jewish, ethical, and philosophical enrichment. One of my regular Friday rituals has been to print out Sacks's commentary on the weekly Torah reading. The strikingly insightful commentary and essays in the Jonathan Sacks Haggada have enhanced my Passover seder for years. On a few occasions, I quoted Sacks in a Boston Globe column, such as one in 2013 that explored the question of how evolution could have led to altruism — a virtue seemingly at odds with the principle of survival of the fittest. I look forward to reading his final book, Morality, published just weeks before his death and already an Amazon bestseller.

Though Rabbi Sacks died before he got old (72 seemed old to me once, but not so much anymore), his words will provide enlightenment and uplift for years to come. If you've never read anything he wrote, a treasure awaits you. Here are a few snippets from his prodigious output:

From The Great Partnership: Science, Religion, and the Search for Meaning (2011):

It is no accident that freedom occupies a central place in the Hebrew Bible but only a tenuous place in the annals of science. The relationship of soul to body, or mind to brain, is precisely analogous to the relationship of God to the physical universe. If there is only a physical universe, there is only brain, not mind, and there is only the universe, not God. The non-existence of God and the non-existence of human freedom go hand in hand. . . .

Abrahamic monotheism is based on the idea that the free God desires the free worship of free human beings. The historical drama of the Bible turns on the question of how to translate individual freedom into collective freedom. How do you construct a free society without the constant risk of the strong dominating and exploiting the weak? This is the issue articulated by the prophets, and it was never completely solved. Politics is a problem for the Bible, precisely because it believes that no human being should exercise coercive force over another human being. Politics is about power, and Abrahamic faith is a protest against power.

From "Loving the Stranger," (weekly Torah commentary for February 2, 2008):

There are commands that leap off the page by their sheer moral power. So it is in the case of the social legislation in [Exodus 21-24]. Amid the complex laws relating to the treatment of slaves, personal injury and property, one command in particular stands out, by virtue of (a) its repetition — it appears twice in a single passage — and (b) the historical-psychological reasoning that lies behind it:

Do not ill-treat a stranger or oppress him, for you were strangers in Egypt.

Do not oppress a stranger; you yourselves know how it feels to be a stranger, because you were strangers in Egypt. . . .

According to Nachmanides, the command has two dimensions. The first is the relative powerlessness of the stranger. He or she is not surrounded by family, friends, neighbors, a community of those ready to come to their defense. Therefore the Torah warns against wronging them because God has made himself protector of those who have no one else to protect them. This is the political dimension of the command.

The second reason . . . is the psychological vulnerability of the stranger (we recall Moses' own words at the birth of his first son: "I am a stranger in a strange land"). The stranger is one who lives outside the normal securities of home and belonging. He or she is, or feels, alone – and, throughout the Torah, God is especially sensitive to the sigh of the oppressed, the feelings of the rejected, the cry of the unheard. That is the emotive dimension of the command. . . .

It is terrifying in retrospect to grasp how seriously the Torah took the phenomenon of xenophobia, hatred of the stranger. It is as if the Torah were saying with the utmost clarity: Reason is insufficient. Sympathy is inadequate. Only the force of history and memory is strong enough to form a counterweight to hate.

From the Introduction to the Koren Yom Kippur prayerbook (2014):

Judaism is the world's greatest example of a guilt-and-repentance culture, as opposed to the shame-and-honor culture of the ancient Greeks.

In a shame culture such as that of Greek tragedy, evil attaches to the person. It is a kind of indelible stain. There is no way back for one who has done a shameful deed. He is a pariah and the best he can hope for is to die in a noble cause. In a guilt culture like that of Judaism, evil is an attribute of the act, not the agent. Even one who has done wrong has a sacred self that remains intact. He may have to undergo punishment. He certainly has to make amends. But there remains a core of worth that can never be lost. A guilt culture hates the sin, not the sinner. Repentance, rehabilitation, and return are always possible.

A guilt culture is a culture of responsibility. We do not blame anyone else for the wrong we do. It is always tempting to blame others — it wasn't me, it was my parents, my upbringing, my friends, my genes, my social class, the media, the system, "them." . . .

Blaming others for our failings is as old as humanity, but it is disastrous. It means that we define ourselves as victims. A culture of victimhood wins the compassion of others but at too high a cost. It incubates feelings of resentment, humiliation, grievance, and grudge. It leads people to rage against the world instead of taking steps to mend it. Jews have suffered much, but Yom Kippur prevents us from ever defining ourselves as victims. As we confess our sins, we blame no one but ourselves.

From "Reversing the Moral Decay Behind the London Riots" (The Wall Street Journal, Aug. 20, 2011)

We have been spending our moral capital with the same reckless abandon that we have been spending our financial capital. Freud was right: The precondition of civilization is the ability to defer the gratification of instinct. And even Freud, who disliked religion and called it the "obsessional neurosis" of humankind, realized that it was the Judeo-Christian ethic that trained people to control their appetites and practice the necessary ethic of self-restraint.

There are large parts of Britain, Europe, even the United States, where religion is a thing of the past. . . . The message is that morality is passé, conscience is for wimps, and the single overriding command is "Thou shalt not be found out." Has this happened before, and is there a way back? The answer to both is in the affirmative.

In the 1820s, in Britain and America, a similar phenomenon occurred. People were moving from villages to cities. Families were disrupted. Young people were separated from their parents and no longer under their control. Alcohol consumption rose dramatically. So did violence. In the 1820s it was unsafe to walk the streets of London because of pickpockets by day and "unruly ruffians" by night.

What happened over the next 30 years was a massive shift in public opinion. There was an unprecedented growth in charities, friendly societies, working men's institutes, temperance groups, church and synagogue associations, Sunday schools, YMCA buildings, and moral campaigns of every shape and size. . . . The common factor was their focus on the building of moral character, self-discipline, willpower and personal responsibility. It worked. Within a single generation, crime rates came down and social order was restored. What was achieved was nothing less than the re-moralization of society – much of it driven by religion.

It was this that the young French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville saw on his visit to America in 1831. It astonished him.

Here is something to view, not to read: In 2017, Sacks narrated a YouTube whiteboard animation — "On the Mutation of Antisemitism." It is an effective and compelling explanation of the oldest hatred known to history. Click below to watch:

Finally, from the acknowledgments page at the end of A Letter in the Scroll (2000):

My father was a simple man who lived by simple truths. He had a hard life; he came to the West as a child fleeing from persecution, and he had to leave school at the age of 14 to support his family. When I was young, I used to ask him many questions about Judaism, and his answer was always the same. "Jonathan," he used to say "I didn't have an education, and so I do not know the answers to your questions. But one day you will have the education I missed, and then you will teach me the answers." Could anyone have been given a greater gift than that? . . . I dedicate this book to his memory.

Jonathan Sacks lived an extraordinarily fruitful and meaningful life, and left the world better than he found it. May his memory be a blessing for generations to come.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter or on Parler.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.