Give thanks for the Pilgrims and private property

Most Americans know the rudiments of the Thanksgiving story: How the Pilgrims suffered through that first year in the place they called Plymouth. How food and shelter were so inadequate during the bitter winter of 1620-21 that most of the small company grew sick and half its members died. How the survivors struggled to get the seeds they had brought from Europe to grow in the stony Massachusetts soil and how they might have starved if kindly Indians hadn't taught them to plant corn. How they were grateful for the first small harvest they managed in the summer of 1621, and for the abundance of fish and game with which they were able to supplement it.

It was to celebrate that initial harvest that Governor William Bradford authorized a community feast and invited the neighboring Indians — the Wampanoag sachem Massasoit and about 90 of his warriors — to "rejoice together" over venison and wild fowl. "All had their hungry bellies filled," Bradford would later write in Of Plymouth Plantation. Today we look back to that harvest feast of 1621 as the first American Thanksgiving.

But 1621 wasn't a turning point and the celebrants at that "first Thanksgiving" didn't celebrate for long. Bellies were soon empty again. Plymouth Plantation was failing — and not because of bad weather or stony soil.

It was human nature, not Mother Nature, that threatened the settlers with destitution. The settlement at Plymouth was a commercial enterprise but it operated, in effect, as a religious commune. The terms of the agreement by which the colony had been chartered, signed in London before the Mayflower sailed, were strict: "All profits and benefits that are got by trade, traffic, trucking, working, fishing, or any other means" were to become part of "the common stock." Moreover, "all such persons as are of this colony are to have their meat, drink, apparel, and all provisions out of the common stock and goods of the colony."

As Nick Bunker writes in Making Haste from Babylon, his acclaimed 2010 history of the Mayflower Pilgrims and their world,

for the first seven years no individual settler could own a plot of land. To ensure that each farmer received his fair share of good or bad land, the slices were rotated each year, but this was counterproductive. Nobody had any reason to put in extra hours and effort to improve a plot if next season another family received the benefit.

To all intents and purposes, in other words, there was no private ownership. No one's labor resulted in benefit for themselves or their family, so no one was motivated to work harder or more diligently. Whatever any individual produced would belong to all, and he would be entitled to get back only what was deemed necessary for him and his family. As Karl Marx would phrase it 255 years later, "from each according to his abilities, to each according to his need." Communism was destined to fail in 20th-century Europe, China, and Cuba. It fared no better in 17th-century Massachusetts.

The system "was found to breed much confusion and discontent and retard much employment," Bradford recorded. "For the young men that were most fit for labor and service did repine that they should spend their time and strength to work for other men's wives and children without any recompense. The strong . . . had no more in division of victuals and clothes than he that was weak and not able to do a quarter [of what] the other could; this was thought injustice. . . . And for men's wives to be commanded to do service for other men, as dressing their meat, washing their clothes, etc., they deemed it a kind of slavery; neither could many husbands well brook it."

Bad attitude led to bad crops — and worse. "Much was stolen both by night and day," Bradford wrote of the 1622 harvest. "And although many were well whipped . . . yet hunger made others, whom conscience did not restrain, to venture." It became clear that unless something changed, "famine must still ensue the next year also."

It didn't take long for the settlers to understand the built-in disincentives of the system they were operating under. The lack of private property, they realized, was stifling productivity and bringing out the worst in their characters. So in the spring of 1623, communism was replaced with capitalism.

As Bradford later recorded, it was decided to alter the rules, and to "set corn every man for his own particular, and in that regard trust to themselves. . . . And so assigned to every family a parcel of land. . . . This had very good success, for it made all hands very industrious, so as much more corn was planted than otherwise. . . . The women now went willingly into the field and took their little ones with them to set corn."

The "first Thanksgiving" in 1621 notwithstanding, Plymouth Plantation struggled to feed its members until the communal system was replaced with one based on private property. |

The results were outstanding. In 1621, the colony had planted just 26 acres. In 1622, it planted 60. But in 1623, with families now working for themselves, 184 acres were planted.

When the harvest season came, Bradford later wrote, "instead of famine, now God gave them plenty, and the face of things was changed to the rejoicing of the hearts of many, for which they blessed God." The effect of switching from communal to private property "was well seen," Bradford noted — so much so that "any general want or famine hath not been amongst them since to this day." Before long, Plymouth was exporting corn.

The Pilgrims had tried to survive under socialism avant la lettre, and they met the disappointing results socialism always engenders. The introduction of private property and self-interest transformed that disappointment into success — something that has "happened so often historically it's almost monotonous," as Lawrence W. Reed remarks in an essay for the Foundation for Economic Education:

Over the centuries, socialism has crash-landed into lamentable bits and pieces too many times to keep count — no matter what shade of it you pick: central planning, welfare statism, or government ownership of the means of production. Then some measure of free markets and private property turned the wreckage into progress. I know of no instance in history when the reverse was true — that is, when free markets and private property produced a disaster that was cured by socialism. None.

A few of the many examples that echo the Pilgrims' experience include Germany after World War II, Hong Kong after Japanese occupation, New Zealand in the 1980s, Scandinavia in recent decades, and even Lenin's New Economic Policy of the 1920s.

It might be overstating the case to claim that the experience of the Plymouth colonists four centuries ago inoculated Americans against socialism. But it is fair to say that mainstream America has never been tempted by the socialist claim that letting government control all property and direct the economy will lead to prosperity. There is a Socialist Party in the United States and there have always been some candidates who preach the virtues of socialism. It isn't hard to find ardent proponents of socialist nostrums on college campuses, in the media, and especially in the entertainment industry.

Nonetheless, most Americans know better. They perceive that wherever socialism has been imposed, its failures have been comprehensive: more poverty, less freedom, fewer resources, crippled agriculture, stunted growth, rising authoritarianism, and heartbreaking desperation. In just the last few years, socialism has destroyed Venezuela, turning the country with the highest standard of living in Latin America into an impoverished basket case.

The great economic lesson of Plymouth's early years is one that cannot be taught too often: Private ownership and a free market are indispensable to prosperity. The "first Thanksgiving" was in 1621, but the crucial insight — the one that rescued Plymouth from economic calamity and made possible the eventual emergence of American liberty — occurred two years later. The embrace of private property in Massachusetts was a godsend, one whose blessings we reap to this day. Let us give thanks.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Urging Jews to accept Jesus isn't antisemitic. It's Christian.

Madison Cawthorn is a 25-year-old congressman-elect from North Carolina's 11th congressional district. He is a Republican, a paraplegic, a social conservative, a real estate investor, a motivational speaker, and soon to be the youngest member of Congress in nearly six decades.

He is also a fervent Christian.

"I would say I have a very, very, very strong faith," Cawthorn told reporter Matthew Kassell during an interview for Jewish Insider, "and [I am] very grounded in the actual Word."

Representative-elect Madison Cawthorn |

That interview made news last week because Cawthorn said he has tried to convert people to Christianity, and that he's read the Torah and the Quran in hopes of using that knowledge to proselytize to Jews and Muslims. He has converted "several Muslims to Christ," he claims, but has met with less success when he has reached out to Jews. From the article:

"If all you are is friends with other Christians, then how are you ever going to lead somebody to Christ?" Cawthorn mused. "If you're not wanting to lead somebody to Christ, then you're probably not really a Christian."

Had he ever tried to convert any Jews to the Christian faith?

"I have," he said with a laugh. "I have, unsuccessfully. I have switched a lot of, uh, you know, I guess, culturally Jewish people. But being a practicing Jew — like, people who are religious about it— they are very difficult. I've had a hard time connecting with them in that way."

Is there anything wrong with that? Not in the least. But from the cries of "Antisemitism!" that erupted after Cawthorn's remarks were published, you'd have thought he was rounding up Cossacks to stage a pogrom. A few examples:

- From BuzzFeed reporter Julia Reinstein: "[G]enuinely frightening levels of antisemitism from an incoming member of Congress!"

- From Jewish Daily Forward columnist Alex Zeldin: "Targeting Jews for conversion is antisemitic, hope that clears things up for anyone who was confused."

- From MSNBC host Chris Hayes: "In all seriousness this is a really antisemitic thing to say, it's like the original antisemitic thing to say and doesn't rely on any codes or tropes. And the entire GOP should condemn it."

- From the Jewish Democratic Council of America: "Madison Cawthorn . . . discussing converting Jews to Christianity" proves that "the GOP is normalizing and emboldening antisemitism."

Those are indecent and indefensible accusations — bad enough if they stem from ignorance, far worse if from partisanship.

Inviting Jews to convert to Christianity is not antisemitic. In the long history of the Jewish people, there have, of course, been many grim chapters in which Jews were forced to convert, on pain of death or expulsion, and it goes without saying that such intolerant cruelty was antisemitic to the core. Antisemitic too were the severe disabilities to which Jews who wouldn't renounce their faith were often subjected, both in Christendom and the Muslim world — social ostracism, bans on engaging in businesses, residential segregation, legal double standards, punitive taxes.

But what has any of that to do with Christians in America, a nation that protects freedom of religion (including the freedom to reject religion), and where Judaism has flourished for generations alongside numerous other faiths? Evangelicals — or, for that matter, Mormons or Shiites or Hindus or atheists — who try to win Jews over to their own beliefs are doing nothing wrong. And to accuse them of bigotry and religious hatred is outrageous.

As an observant Jew, I am not offended in the least when courteous and respectful Christians try to awaken in me an interest in their religion. To be sure, I don't share their conviction that Jesus was the messiah, or even a prophet. Judaism rejects the very notion of a God Incarnate or of the Trinity — it is fundamental to Jewish belief that God has no physical form and that God's unity is singular and indivisible. But if Cawthorn seeks to persuade me to change my mind, he has every right to do so without being smeared as an antisemite.

It is a widely held article of Christian faith that no one can be spiritually saved except through Jesus, and that Christians are bound to spread this "good news" — the literal translation of "gospel" — to those who haven't accepted it. By their lights, proselytizers are offering Jews something incalculably precious: eternal salvation. My religion does not require me to go out and convert people. Indeed it discourages it (although sincere and self-motivated converts to Judaism are welcomed and honored). But I have no problem with the dedication of Christians who take to heart their own faith's injunction to turn hearts and minds to Jesus.

Then again, as Cawthorn has discovered, Jesus is a tough sell to Jews. We are a notoriously fractious breed, but if there is one thing on which Jews broadly agree, it is that anyone who believes in Jesus is not a Jew. That is true even of people who are only "culturally" Jewish — i.e., they are Jewish in the sense that they consider themselves ethnically or communally Jewish, not because they practice Judaism or embrace Jewish religious beliefs. In its in-depth 2013 survey of Jews in America, the Pew Research Center found that only 19% of American Jews considered observance of Jewish law essential to being Jewish, and only 29% felt that way about belief in God. Yet a whopping 60% of American Jews agreed that refusing to believe that Jesus was the messiah is indispensable to being Jewish.

(As an aside, this is why those who call themselves "messianic Jews," such as Jews for Jesus, are almost universally shunned by the Jewish community. They are not Jews, but Christians sailing under a false flag. However friendly and devout and "Jew-ish" they may be, they are not part of the Jewish community. At the core of "Jewish messianism" is the assertion that Jews should abandon some of the most fundamental and normative Jewish doctrines — that it is forbidden to worship any person, that the Torah cannot be superseded by a "new" testament, and that the messiah has not come. "Jews for Jesus" is a contradiction in terms, and the organization bearing that name is not Jewish.)

Over the years I have periodically been approached by missionaries hoping to engage my interest in Christianity. At the risk of generalizing, I have generally found them to be more enthusiastic about their religion than knowledgeable in it, and to be prepared with talking points, not with arguments rooted in years of study. That always made it easy for me to politely deflect their approach, sometimes by simply responding to their questions with questions of my own. ("If the messiah is to bring universal peace to the world, how could Jesus have been the messiah?") I was raised with the benefit of a Jewish education, which is the most effective antidote to the blandishments and contentions of missionaries. Anyone disturbed by Christians seeking converts among the Jews should promote Jewish schooling for Jewish children, rather than smear proselytizers as antisemites.

There is no contradiction between my liberty to practice my religion and the liberty of even the most earnest evangelizing Christians to practice theirs. As Americans, we respect each other's freedom — theirs to say "Come to Jesus," mine to say "No, thank you."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The case for curfews is nonexistent

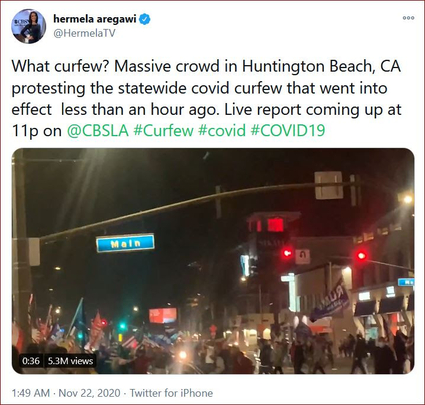

Did you know that the coronavirus, like vampires and werewolves, is deadliest after dark? I didn't either, but it must be true. What other justification can there be for the imposition of curfews on residents and businesses in Massachusetts, Ohio, New York, and elsewhere by governors who claim their purpose is to control the spread of COVID-19?

In Massachusetts earlier this month, Governor Charlie Baker issued his 53rd "emergency" order , requiring 16 categories of facilities — from restaurants, arcades, golf courses, and drive-in theaters to gyms, zoos, flight schools, and museums — to close their doors to the public by 9:30 each night. Though the order is 5½ single-spaced pages long, it contains not a single sentence explaining how Massachusetts will be better protected from the coronavirus if residents who are permitted to go out for pizza or to work out at 7:45 pm are barred from doing so at 9:45 pm. Neither does the accompanying "advisory ," which counsels all residents of the state to stay home between 10 pm and 5 am.

"Taking these steps is critical to preventing the spread of the virus, protecting the lives of you and your loved ones, and preserving our acute care hospital and other health care systems' capacity," the advisory asserts. But it provides no evidence to back up that assertion.

That's because there is none. Masks, physical distancing, and capacity limits all have a direct and articulable relevance to reducing exposure to the virus. Curfews don't. If going out for a drink or a walk isn't dangerous before 10 pm, it isn't dangerous after 10 pm.

There is no data — none — to show that criminalizing a late-night dinner will bring down infection rates or hospitalizations. William Hanage, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, told USA Today that he is skeptical curfews will do anything to curb attacks of the virus:

"Curtailing the evening for dining by an hour or so isn't likely to make a very large impact," Hanage said. "I can't think of a single place where further action was not necessary."

He concedes a curfew may cut down on alcohol-induced bad decisions but he worries that people kicked out of bars and restaurants at 9:30 pm will congregate in small, airless apartments, where the risk of infection will be even higher.

Another epidemiologist, Jennifer Weuve of Boston University's School of Public Health, called curfews a "blunt instrument" that will prove far less effective than more carefully targeted limitations, such as disallowing indoor restaurant dining:

Curfews just add to public confusion about what is potentially dangerous behavior and what isn't, she said.

Dining outdoors at 10 pm isn't riskier than at 7 pm, but eating in a crowded restaurant is dicey no matter what time of day, Weuve said.

Al Tompkins, a senior faculty member at the Poynter Institute, a journalism school and research institute, cannot make sense of the curfew orders, and is dismayed that reporters are showing so little skepticism about them:

Even if you do believe that it makes sense to impose curfews on bars, why are so many local governments also imposing the restrictions on gyms? Is there some rowdy behavior happening in gyms after 10 pm? It seems like it would be safest to work out then, when hardly anybody is around.

Connecticut is also forcing bowling alleys and movie theatres to close by 10 pm while Massachusetts added hair salons to its 9:30 pm curfew that also includes bars, gyms, and theaters. Why?

All I am asking is for you journalists to ask questions when governments impose restrictions on businesses. Maybe we should listen to people who are angry that governments are overreaching on some things while being too timid on others. It seems to me you should be asking for some evidence that each restriction has a real scientific basis, such as those that exist for limiting crowds and wearing masks.

To the extent that curfews have any rationale at all, it is that by shrinking the hours of operation at venues where people might not be diligent about masking or distancing, the virus will have less opportunity to spread. In other words, if patrons can't drink in a bar or run on the treadmill at a gym after 10 pm, then at least after 10 pm the virus will be doing less damage.

"But there's no evidence that this is indeed the case," Elizabeth Nolan Brown observes in Reason:

And it's just as likely that limited hours mean more people cramming their shopping, socializing, and errands into the same hours, making establishments more crowded and ensuring longer waits in transmission-friendly lines. Besides, not everyone has a job or home and family responsibilities that make state-approved socializing hours possible. Making residents stay in their homes after a certain hour eliminates people's ability to meet non-household members in safer ways — like taking walks together, meeting in yards or on porches, or patronizing places where the weather or heat lamps still permit — and it also invites selective and discriminatory enforcement.

Brown calls the curfews "hygiene theater" — directives intended to convey the appearance of strong public-health measures without any of the substance. It's all for show, neither reducing the spread of the virus, nor eliminating risky behavior. Their purpose, it appears, is merely to communicate the message that the pandemic is getting worse and government is taking action. That it isn't effective is beside the point.

As has been the case with pandemic restrictions for months, these curfews take the form of unilateral decrees from governors. In Massachusetts, they continue to be issued without any meaningful public input, without any deliberation by the Legislature, and without any due process for individuals whose lives and businesses are being damaged. It isn't even clear that the orders are legitimate — a lawsuit challenging Baker's authority to promulgate such directives under state law has been pending before the Supreme Judicial Court for months.

Defeating the coronavirus is a crucial public priority. But that is no reason to infringe personal liberty and disrupt economic life with restrictions that cannot be scientifically or logically justified. The curfews are foolish and likely counterproductive. Why aren't more public voices saying so?

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter or on Parler.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.