ON THE FOOD NETWORK, I've noticed, contestants and judges on shows like "Chopped" and "Guy's Grocery Games" routinely address each other as "Chef." As in: "Chef Lisa, tell us what you've made." Or: "Today, chefs, I have prepared for you a broccoli rabe and cheddar-beer soup."

The title of "chef" is earned in the kitchen, and in a culinary setting or a gathering of chefs it is entirely proper to use that appellation. But if I encountered Bobby Flay or Jacques Pépin or Nigella Lawson at a social function or in the grocery store, it would never occur to me to address them as "Chef." And if they were to make a fuss, insisting that everyone should address them that way, I would find their pretentiousness embarrassing and might wonder why their self-esteem was so low.

I feel much the same way about people with academic doctorates who insist on being called "doctor" in non-academic settings.

Jill Biden isn't a doctor. Neither is Henry Kissinger or "Dr." Phil. |

That topic was thrust into the spotlight this weekend when the Wall Street Journal published an opinion column by Joseph Epstein, a prolific author who has written hundreds of essays and stories, and scores of books, including a 2003 bestseller titled Snobbery: The American Version. Epstein's piece took aim at Jill Biden, the wife of the incoming president, who has a Doctor of Education degree, on the strength of which she is frequently referred to, and refers to herself, as "Dr. Biden."

Epstein's essay advised her to give up the honorific.

"Madame First Lady — Mrs. Biden — Jill — kiddo: a bit of advice on what may seem like a small but I think is a not unimportant matter," he began.

Any chance you might drop the "Dr." before your name? "Dr. Jill Biden" sounds and feels fraudulent, not to say a touch comic. Your degree is, I believe, an EdD, a doctor of education, earned at the University of Delaware through a dissertation with the unpromising title "Student Retention at the Community College Level: Meeting Students' Needs." A wise man once said that no one should call himself "Dr." unless he has delivered a child. Think about it, Dr. Jill, and forthwith drop the doc.

"Jill" and "kiddo" were a blunder. Biden is 69, and in the absence of a longstanding friendship with her, Epstein has no business addressing her by her first name, let alone with a faintly patronizing label like "kiddo." Mocking the title of her dissertation was also unworthy. For all Epstein knows, it was a brilliant piece of scholarship. Even if it wasn't, his sneering reference to its prosaic title is just bad manners. He probably thought he was being charming in a curmudgeonly way. I have read many of Epstein's essays in Commentary magazine over the years, and can affirm that he often makes that mistake. (His fiction, in my humble opinion, is much better than his social commentary.)

This being 2020, Epstein was immediately assailed as a "sexist" and a "misogynist ," including in an official statement from Northwestern University, where Epstein taught in the English Department for 30 years. Northwestern went so far as to remove Epstein's profile from its website. Apparently the university considers it intolerable to publicly acknowledge that someone who expressed a criticism of the next First Lady spent three decades of his life instructing Northwestern students.

Millions of Americans have doctoral degrees. That doesn't make them doctors. |

I think it's a stretch to indict Epstein for misogyny — i.e., hatred of, or prejudice against, women — since the argument he was making had nothing to do with Biden's sex. But Epstein should have made that explicit by citing examples of men who have no business being addressed as "doctor." Because their numbers are legion, too.

I argue for a straightforward rule: In ordinary social settings, a "doctor" is someone with a medical or dental degree and a job related to preserving health or curing the sick. Anthony Fauci and Deborah Birx are doctors. Jill Biden and Henry Kissinger aren't. Dr. Oz (thoracic surgery) — doctor. "Dr. Phil" (psychology) — not a doctor. Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson, a Johns Hopkins-trained pediatric neurosurgeon who specialized in traumatic brain injuries, brain and spinal cord tumors, achondroplasia, and congenital disorders, is definitely a doctor. Former Trump White House advisor Sebastian Gorka, who has a degree in political science and likes to be called Dr. Gorka, definitely is not.

I earned a Juris Doctor, but I'm not a "doctor." Neither is my brother, who has a PhD in chemistry. Neither are our 4 million or so fellow JDs and PhDs in the United States, not to mention the countless others who have earned a DM, a PharmD, a DD, a DArch, a DEng, a DFA, or any of the dozens of other research doctorates and professional doctorates awarded by institutions of higher education.

Yes, all those degrees have the word "doctor" in their name, but in this context that means nothing. Receiving a doctorate doesn't mean you should be addressed as "doctor" any more than receiving a master's degree means you should be addressed as "master." Outside of academia, using the honorific "doctor" conveys a specific meaning — that the person referred to has been trained in medicine (or dentistry), and, as a rule, has proven his or her qualifications by treating patients and being instructed in an array of medical specialties. That understanding does not extend to people who are "doctors" of fine arts or education or philosophy. By analogy, Americans routinely honor those who "wear the uniform." That doesn't mean we hold airline pilots or hotel doormen in high esteem just because they, too, wear uniforms.

Political and media circles are filled with people who have non-medical doctorates. Examples include columnist George Will; MSNBC host Rachel Maddow; Senators Ben Sasse, Tammy Duckworth, and Kyrsten Sinema; incoming Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen; former Fed chairmen Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke; former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, and former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright. To my knowledge, none of them has ever insisted on being referred to as "doctor" in daily life.

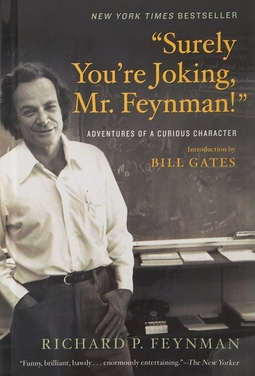

Neither do countless scientific luminaries with doctoral degrees. Richard Feynman (whom I wrote about in Arguable last May) was a Nobel laureate who was one of the most renowned theoretical physicists of the 20th century. He was also perfectly content to be addressed as "mister." Indeed, he titled his 1985 collection of reminiscences "Surely you're joking, Mr. Feyman!"

The overwhelming majority of men and women with non-medical doctorates seem to manage just fine without needing to hear themselves addressed as "doctor." Can't Biden?

Maybe not. More than a decade ago, the Los Angeles Times recounted Joe Biden's explanation that "his wife's desire for the highest [academic] degree was in response to what she perceived as her second-class status on their mail."

"She said, 'I was so sick of the mail coming to Sen. and Mrs. Biden. I wanted to get mail addressed to Dr. and Sen. Biden.' That's the real reason she got her doctorate," he said.

I suppose Biden was joking. But there is usually a kernel of truth in such jokes. My impression is that when non-medicos insist on being called "doctor" outside of academia, they are doing so because of vanity or insecurity.

On campus, the use of "doctor" (or "professor" or "dean") for people who aren't physicians is common, and there is nothing wrong with expecting students or colleagues to address you with such terms. But like Food Network personalities hailing each other as "chef," or an enlisted man on an Army base being called "corporal," what is appropriate within a specific professional milieu becomes pompous outside it.

A brilliant scientist and a Nobel laureate. But not a doctor. |

During the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation hearings in 2018, references to Christine Blasey Ford as "Dr. Ford" were almost ubiquitous. NPR, to its credit, declined to identify the woman who accused Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her in high school as "doctor." It explained its policy, which is essentially the one I have outlined here:

Longstanding NPR policy is to reserve the title of "doctor" for an individual who holds a doctor of dental surgery, medicine, optometry, osteopathic medicine, podiatric medicine, or veterinary medicine.

That excludes those with other types of doctoral degrees, including Christine Blasey Ford. . . .

Ford . . . is a "professor and research psychologist in Northern California at Palo Alto University and the Stanford University PsyD Consortium, a clinical psychology program where she teaches statistics, research methods and psychometrics." She holds a PhD in Educational Psychology from the University of Southern California.

For some listeners, the disparity of hearing Kavanaugh called "Judge Kavanaugh," at times, and not hearing Ford referred to as "doctor" rankled. One called it "offensive," saying it showed how women are disrespected in relation to men. Another called it an "insidious bias." . . . [But] as NPR's standards editor Mark Memmott [said]: "The idea is that for most listeners a 'doctor' practices medicine." The language policy is based on the standard laid out by the AP Stylebook, which many news outlets, including NPR, follow.

Epstein's Wall Street Journal was tone-deaf and sloppily argued, but his basic point is one I think most Americans would agree with: If you don't heal the sick or care for patients, don't expect to be called "doctor." That title should be saved for people who step up when, in an emergency, someone calls out, "Is there a doctor in the house?"

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Have yourself a Jewish little Christmas

For Jews in old Europe, the Christmas season was a time to be watchful and wary and to keep out of sight. For their descendants in America, the Christmas season — which is also the season of Chanukah, of course — is a time to celebrate and give thanks for the freedom of religion that protects the menorah in their living room window no less than the Christmas tree in their neighbor's.

In medieval and early modern Europe, this time of year often brought sermons filled with invective against Jews for the supposed crime of crucifying Christ. Instead of "good tidings of great joy," there were apt to be blood libels and pogroms. In some Polish and German communities, Jews referred to Christmas Eve as Vay Nacht (Woe Night), a bitter play on Weihnahchten , the German word for Christmas. So great was the fear of antisemitic violence that rabbis in many communities took the radical step of prohibiting Jews from studying Torah on Christmas, in order to keep them from going to the synagogue or the study hall. Hatred of Jews polluted even Christmas music: As recently as 2013, Romanian public TV broadcast a program in which a folk ensemble sang a Christmas carol with hideous lyrics about burning Jews:

A beautiful child was born/ His name was Jesus Christ/ All the world worships him / But the kikes / Damn kikes / Holy God would not leave the kike alive / Either in the sky or on the earth / Only in the chimney as smoke / This is what the kike is good for / To make kike smoke through the chimney on the street.

How blessedly different is Christmas in the United States!

This season more than any other underscores the uniqueness of America's Judeo-Christian tradition. Notwithstanding all our political differences, notwithstanding the endless recriminations and acrimony of the culture wars, notwithstanding even the sharp rise of irreligion in recent decades, America remains a nation in which religious tolerance, both legal and social, is deeply rooted. By and large, Americans of every confession — Christians, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, Sikhs — treat each others' religions with courtesy.

That tolerance is a reflection of the fact that religion in America has always been a matter of individual choice, with government barred by the Constitution from either establishing an official faith or prohibiting the free exercise of any faith. No religion is funded by government. Elected officials have no say in the doctrine of any faith or the content of any religious service. Religion has flourished in America because church and state are separate. And it flourishes in peace because no one is forced to support anyone else's faith, or to attend a church he isn't happy with, or to bring up children according to the religious views of whichever faction has the most votes.

In short, religion in America is peaceful because it is government-free. And that, in turn, is a principal reason why, in this overwhelmingly Christian country, it isn't only Christians for whom Christmas is a season of joy. And why it isn't only Christians who should make a point of saying so.

Jews like me, who have grown up amid this religious acceptance, may be inclined to take it for granted, but imagine how extraordinary it must have seemed to Jews who immigrated to America from lands where Christmas was Vay Nacht, or whose parents recalled all too vividly the fear and anxiety that this season used to evoke when they still lived in Poland, Hungary, or Lithuania. Perhaps that explains why so many of America's most beloved Christmas songs were written by Jewish immigrants or their children.

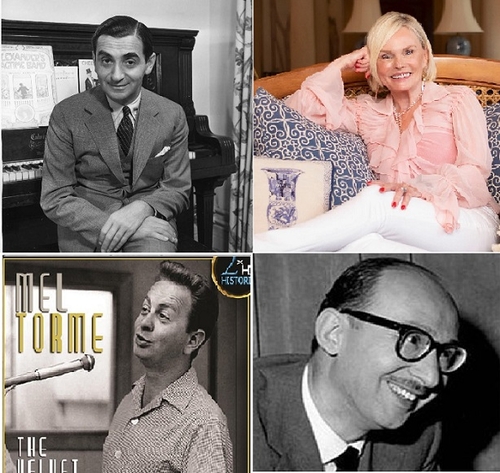

Irving Berlin, Joan Javits, Sammy Cahn, and Mel Tormé — four of the many Jews who helped create the Great American Christmas Songbook |

Think, for example, of Israel Beilin, who was born in the Siberian village of Tyumen in 1888 and immigrated to America as child. He grew up as "Irving Berlin," and went on to compose more than 1,500 songs and score dozens of musicals and films — but nothing he ever wrote proved more popular and enduring than a 1942 song first recorded by Bing Crosby: "White Christmas." It is the best-selling single in the history of recorded music, and it is impossible to imagine the Great American Songbook — let alone the American Christmas Songbook — without it. It evokes what have become classic Christmastime themes: home, childhood, and nostalgia. But in its minor chords, as composer Rob Kapilow has shown, is also "all the yearning of an immigrant to be assimilated."

Berlin was the first of a long line of Jewish immigrants, or their children and grandchildren, who helped create the soundtrack of Christmas in America.

Almost as iconic as "White Christmas" is "The Christmas Song" ("Chestnuts roasting on an open fire / Jack Frost nipping at your nose"). It was written in 1945 by 19-year-old Mel Tormé, the son of Jewish immigrants from Poland, together with his Jewish partner and lyricist, Robert Wells. The following year it was recorded by Nat King Cole, and almost at once became a Christmas classic.

Ray Evans and Jay Livingston were the Jewish songwriting duo who composed "Silver Bells" for a Paramount Pictures film called "The Lemon Drop Kid." They were reluctant at first, Evans recalled years later, because "we figured — stupidly, thank God — that the world had too many Christmas songs already." The song they wrote became a standard, recorded by artists as different as Doris Day, The Temptations, Johnny Mathis, and Elvis Presley.

"Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer" was written by Johnny Marks, another Jewish songwriter. That song alone would have guaranteed that Marks would go down in history, but he also created "I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day" (which is based on an 1863 poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow); " Rockin' Around the Christmas Tree," which has sold tens of millions of copies since it was first recorded by Brenda Lee in 1958; and "A Holly Jolly Christmas," which hit No. 10 on the Billboard "Hot 100" as recently as January 2020 — 58 years after it was composed.

The list goes on and on. Eddie Pola, whose parents were Jewish immigrants from Hungary, wrote "It's the Most Wonderful Time of the Year." Felix Bernard created "Winter Wonderland," which has been covered by hundreds of performers, including Michael Bublé and the Eurythmics. From Walter Kent (originally Walter Kaufman) came "I'll Be Home for Christmas," a beloved song that astronauts Frank Borman and Jim Lovell requested NASA to play for them while they orbited the earth aboard Gemini 7 in December 1965.

Sammy Cahn and Jule Styne were both born to Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe (Galicia in Cahn's case, Ukraine in Styne's). During a heat wave in Hollywood in 1945, the duo wrote "Let It Snow," which doesn't actually mention Christmas but has long since earned a spot on the Christmastime playlist. Another pair of Jewish songwriters, Joan Javits and Philip Springer, came up with "Santa Baby," which was first recorded by Eartha Kitt and became the best-selling Christmas song of 1953 — despite being banned in some states because of its slightly suggestive lyrics. ("I'll wait up for you, dear Santa baby, so hurry down the chimney tonight.")

One last example: Gloria Adele Shain was born in Brookline, Mass.; her family lived next door to Joseph and Rose Kennedy and their children (one of whom was John F. Kennedy). In 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, she wrote the music to "Do You Hear What I Hear?" which was intended as a plea for peace. Today, Kennedy and the Missile Crisis are practically ancient history, but Shain's beautiful song lives on and is heard every year at this time.

In my Jewish home we don't celebrate Christmas, but I enjoy seeing my Christian neighbors celebrate it. I like living in a society that derives so much happiness from its religious holidays. For my ancestors in Europe, the sights and sounds of Christmas could be menacing, but for me and my family — thoroughly Jewish and thoroughly American — they are reassuring and joyful. I am thankful for the freedom that makes that possible, and that inspired so many of the season's songs.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

ICYMI

In my Sunday column , I commemorated the upcoming 250th anniversary of Ludwig van Beethoven's birth by exploring why he remains the most admired composer in the history of Western music. Much of the reason, of course, is the expressive power and sweep of his music, which ranges across the spectrum of emotional experience. Countless listeners have been stirred, too, by the poignancy of Beethoven's biography — the brilliant, driven composer who lost his hearing, yet composed some of the most titanic works in musical literature. In addition, Beethoven has long been regarded as a champion of freedom and a foe of tyranny — the composer to whose music people have turned when liberty was at stake. Two hundred fifty years after his birth, Beethoven stands alone.

As a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination, I noted in Wednesday's column , Joe Biden vowed that he would never issue a pardon to Donald Trump. I suggested he might want to rethink that commitment and emulate President Gerald Ford, who in 1974 granted Richard Nixon a "full, free, and absolute pardon" for any crimes he committed as president. At the time, there was a furious political backlash. But history's verdict is that Ford was right — that his pardon of Nixon was statesmanlike and courageous, helping the nation heal after the turmoil of Watergate. Perhaps Biden should pardon Trump for similar reasons. Trump doesn't deserve magnanimity, but the nation cannot endure a continuation of the poisonous recriminations of the last four years.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter or on Parler.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.