What was the point of Jussie Smollett's hoax?

Long before a Chicago jury on Thursday pronounced Jussie Smollett guilty of five felony counts of disorderly conduct for faking a racist, anti-gay, right-wing assault and then lying about it to police, it was clear to anyone with a standard IQ — at least anyone not blinded by ideology — that the shocking crime the former "Empire" actor reported in January 2019 had been a sham.

As skeptics noted virtually from the outset, pretty much every element of Smollett's story was preposterous. Nothing about it passed the smell test, from the assailants toting a noose and bleach through the subzero streets of Chicago at 2:00 AM to the claim that they yelled "This is MAGA country!" in a city that went 83 percent for Hillary Clinton in 2016.

And yet, preposterous as it was, some of the most prominent progressives in US politics — including several who at the time were running for president — lined up to denounce the thugs who had supposedly ambushed Smollett. Many of them unquestioningly portrayed the attack as an illustration of the kind of hateful bigotry that is endemic in America.

Some examples:

Joe Biden: "What happened today to Jussie Smollett must never be tolerated in this country. We must stand up and demand that we no longer give this hate safe harbor; that homophobia and racism have no place on our streets or in our hearts. We are with you, Jussie."

Kamala Harris: "Jussie Smollett is one of the kindest, most gentle human beings I know. I'm praying for his quick recovery. This was an attempted modern day lynching. No one should have to fear for their life because of their sexuality or color of their skin. We must confront this hate."

Bernie Sanders: "The racist and homophobic attack on Jussie Smollett is a horrific instance of the surging hostility toward minorities around the country. We must come together to eradicate all forms of bigotry and violence."

Cory Booker: "The vicious attack on actor Jussie Smollett was an attempted modern-day lynching. I'm glad he's safe. To those in Congress who don't feel the urgency to pass our Anti-Lynching bill designating lynching as a federal hate crime – I urge you to pay attention."

Pete Buttigieg: "While the struggle for basic hate crime legislation continues here in Indiana, this horrible attack calls all Americans to stand against hatred and violence in all its forms."

Tom Perez: "Let's call it what it is: A vicious hate crime. My heart goes out to Jussie's family — all of us at the DNC are praying for his full recovery."

Elizabeth Warren: "Racism, homophobia & all forms of bigotry & hate have no place in this country. The fight for equality isn't over – no one should have to live in fear of being beaten on the street because of who they are."

Maxine Waters: "Jussie is my friend — a very talented & beautiful human being. It is so hurtful that homophobic haters would dare hurt someone so loving and giving. I'm dedicated to finding the culprits and bringing them to justice. Jussie did not deserve to be harmed by anyone!"

Beyond the politicians, an equally long list of media figures and entertainment celebrities, from Reese Witherspoon to George Takei to Joy-Ann Reid, took Smollett's story at face value and publicly expressed support for him. And as The Hill's media reporter Joe Concha later noted, many newsrooms were so quick to publicize Smollett's claim and its fallout that they lost sight of basic journalistic practice:

Missing from much of the breathless initial reports was a very key word: Alleged. As in, "the alleged attack."

"Celebrities, lawmakers rally behind Jussie Smollett in wake of brutal attack" — ABC News

"Analysis: The Jussie Smollett attack highlights the hate black gay Americans face" — The Washington Post

"'Empire' star Jussie Smollett attacked in possible hate crime" — CNN

"Empire star Jussie Smollett attacked in Chicago by men hurling homophobic and racial slurs" — NBC News

"Celebrities rally behind Jussie Smollett after brutal attack in Chicago" — Buzzfeed

If this were the first time that a shocking and despicable hate crime turned out to be a hoax or a trumped-up outrage, it would be easier to understand the readiness of so many prominent and savvy people to swallow Smollett's accusations without demur. But it isn't close to the first time.

In an interview on ABC's 'Good Morning America,' Jussie Smollett doubled down on his false claim of being set upon by violent racists: 'I will never be the man that this did not happen to.' |

"Many very high-profile incidents of 'racial hate' have unraveled similarly in recent years," writes Wilfred Reilly, a political scientist at Kentucky State University and the author of Hate Crime Hoax, published in 2019.

The Covington Catholic affair, which was at first alleged to have involved a mob of white high school punks chanting "Build the Wall" at a Native American elder, turned out to have been a shouting match between the high-schoolers and a group of radical "Black Israelites," which the Israelites started. Other incidents that turned out to be fake: Klansmen roaming the bucolic campus of Oberlin College, a white man harassing a black Georgia state representative in a grocery store, racists placing a "noose" in the garage of black NASCAR driver Bubba Wallace, Trump supporters tearing a hijab off of Yasmin Seweid on the New York subway, white bigots urinating on a young black girl in Grand Rapids, white men setting a biracial teenager on fire in Madison, and so on and so on. One could go back farther and add the Duke lacrosse case and the fabricated assault on Tawana Brawley.

Plenty of other incidents the caused a media storm can be added to that roster: The student who falsely accused Smith College of racially profiling her. The eruption of racist graffiti at Oberlin College that turned out to be the handiwork of two progressive students. The black woman in Texas who made up a story about being sexually assaulted by a white state trooper. Inventing hate crimes where none occurred is all too common an occurrence.

Hate-crime hoaxers have different motives. Sometimes their intentions are tawdry or pathetic — to extract money or to gain personal attention. At others times, writes Reilly, a black scholar who teaches at a historically black university, perpetrators claim they staged incidents "to call attention to real incidents of racist violence." But if acts of violent racism are indeed a widespread problem, why the need for deception? In truth, Reilly explains,

hate crime hoaxers are "calling attention" to a problem that is a very small part of total crimes. There is very little brutally violent racism in the modern USA. There are less than 7,000 real hate crimes reported in a typical year. Inter-racial crime is quite rare; 84 percent of white murder victims and 93 percent of black murder victims are killed by criminals of their own race, and the person most likely to kill you is your ex-wife or husband. When violent interracial crimes do occur, whites are at least as likely to be the targets as are minorities. Simply put, Klansmen armed with nooses are not lurking on Chicago street corners.

In this context, what hate hoaxers actually do is worsen generally good race relations, and distract attention from real problems.

Hate crimes hoaxes are particularly contemptible for precisely the reason that hate crimes themselves are so reviled: because their target is not just the falsely accused individual(s), but also the entire population they are meant to alarm or intimidate. In the real world, hate-driven crimes of racial oppression — the kind of bloody, cruel, and frightening acts that were so common during the long era of Jim Crow and enforced segregation — are at a historic low. Trumped-up hate crimes, especially when they are widely covered in the media, cast a shadow over that optimistic truth and instead fuel fears that the haters are everywhere.

Racism and bigotry really do exist, of course. Every society has lowlifes and bullies. But by and large, this is not a nation that conspires to keep minorities — racial or otherwise — down, let alone to terrorize or humiliate them. Once upon a time, the killers of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, James Byrd, and the members of the Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, S.C., would have likely gone free. In today's America, they are convicted of murder and sentenced to very long prison terms — or to death.

It is precisely because America is no longer steeped in the racist oppression of the past that those who insist it is have too often resorted to fakery. And when they do, what is the result? Great outpourings of sympathy, solidarity, and outrage. The very reaction they elicit is evidence that the nation they live in is not an unreconstructed racist hellscape filled — as Bernie Sanders tweeted — with "surging hostility toward minorities around the country."

To repeat, hate crimes are real. But by now we should know not to take accusations of such crimes at face value unless they are accompanied by concrete evidence or ample eyewitness testimony. Because hate-crime hoaxes are real too, and some people are much too eager to believe them.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A reader's Christmas cornucopia

As a traditional Jew, I don't celebrate Christmas. But as an American, I have always liked seeing my neighbors celebrate it and I greatly enjoy the Christmas decorations, Christmas music, and festive Christmastime mood. "I like living in a society that makes a big deal out of religious holidays," I wrote once in a column. "When the sights and sounds of Christmas surround me each December, I find them reassuring. They reaffirm the importance of the Judeo-Christian culture that has made America so exceptional — and such a safe and tolerant haven for a religious minority like mine."

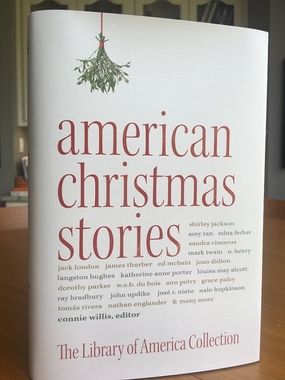

This Christmas season brings something new to celebrate: American Christmas Stories, a Library of America anthology edited by Connie Willis, the renowned science fiction author. It is a collection of 59 stories, each distinctly American and each connected in some way with Christmas. They span 132 years, from Bret Harte's "How Santa Claus Came to Simpson's Bar," which was written in 1872, to Nalo Hopkinson's "A Young Candy Daughter," which appeared in 2004. I confess I had never heard of either of those stories. The same was true of almost all the others in this 450-page volume.

Far from being an anthology of comfortable old favorites, Willis and LOA have compiled a cornucopia of surprising, wide-ranging, provocative, and largely unfamiliar gems. Some are by American authors nearly everyone has heard of — Mark Twain, O. Henry, Ray Bradbury, John Updike. Quite a few are by authors who were entirely unknown to me: John Kendrick Bangs, Margaret Black, Mildred Clingerman, José R. Nieto. Think of everything a traditional Christmas anthology ought to contain. Odds are you won't find it here.

Don't bother looking for "The Gift of the Magi." Instead you'll find "Bethlehem, Dec. 25" (Heywood Broun on word of a momentous birth reaching the newsroom), "Reb Kringle" (Nathan Englander on a mall Santa who is far from typical), and "The Night Before Christmas" (Tomás Rivera on an agoraphobic mother who yearns to buy her children toys but is terrified of the crowds in stores). The Western writer Mari Sandoz recalls "The Christmas of the Phonograph Records," when her father spent a fortune the family couldn't afford to buy the first phonograph in rural Nebraska. The inimitable Damon Runyon, in "The Three Wise Guys," somehow turns a story about bootleggers on the run into an account of a young woman going into labor on Christmas Eve in a Pennsylvania barn.

In "The Christmas Kid" by Pete Hamill, a group of Catholic kids in Brooklyn not long after World War II are introduced to a Jewish newcomer — a thin boy, nine years old, newly arrived from Europe with frightened eyes and a number tattooed on his wrist. In John Collier's "Back for Christmas," a doctor's perfect plan to murder his wife and bury the evidence runs into a Yuletide snag. (That one was so deliciously evil that Alfred Hitchcock filmed it for television.)

In an absorbing introduction to the anthology, Willis surveys the rise of American Christmas stories, which, she explains, were few and far between well into the 19th century.

Then, in the 1860s, three pivotal things happened. The first was the Civil War, which separated 3 million men and boys from their homes and brought grief and loss to the families of more than 600,000 of them. To the soldiers, Christmas became a treasured memory, and to the people back home, a time of remembering loved ones far away . . . .

The second thing to happen was the appearance of a number of pictures depicting Christmas. A pair of engravers, Currier and Ives, who specialized in "engravings for the people" — inexpensive enough for the average family to own — produced a set of hand-colored prints depicting ice-skating on frozen ponds, sleigh rides through snowy landscapes, and jolly homecomings.

At the same time, Thomas Nast, a political illustrator most famous for popularizing the symbols of the Democratic donkey and the Republican elephant, began drawing a series of Civil War-themed cartoons for Harper's Weekly that included a depiction of Santa Claus. . . . Nast's cartoons of Santa Claus gave Christmas a face, Currier and Ives's engravings gave it a setting, and together they brought the image of Christmas into focus for Americans.

Lastly, Charles Dickens came to the States in 1867, on a speaking tour during which he read A Christmas Carol to American audiences for the first time. . . . A Christmas Carol wasn't just any story. It had everything — humor, pathos, drama, redemption, unforgettable characters, and a truly happy ending. It also had ghosts, which had been a Christmas tradition since the Middle Ages. . . . It was the embodiment of everything a Christmas story should be, and Dickens's American audiences loved it.

The coming together of A Christmas Carol, Nast's cartoons, and Currier and Ives's prints had the effect of touching a match to tinder. The celebrating of Christmas — and the writing about it — ignited, and soon Christmas stories by Americans were appearing everywhere.

Some of the stories collected here are funny; others are poignant or tender, dramatic or disturbing. One has become my new favorite: "Christmas Every Day" by William Dean Howells. Published in 1892, it is a highly entertaining story-within-a-story of a little girl who loved Christmas so much that she wanted it to be Christmas every day in the year. She gets her wish, only to learn that there can indeed be too much of a good thing.

American Christmas Stories, on the other hand, is not too much of a good thing. It is a trove of treasures, many long-forgotten, and an elegant addition to the Library of America's series of authoritative American texts. Over time, I imagine many readers will incorporate some of these stories into their yearly Christmas traditions. Who knows? Some may even do what I did this year, and dip into it during Chanukah.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.