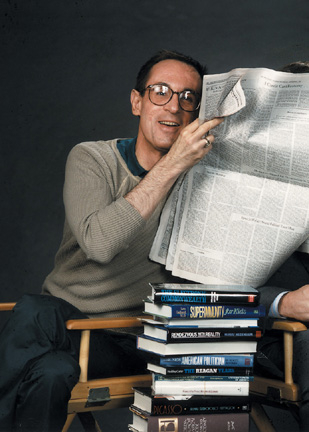

Note for readers outside New England: David Brudnoy, who died last week in Boston of a rare form of skin cancer, was widely regarded as the finest talk-show host in Boston. Learned, warm, civilized, interesting, eclectic, he was described as "the talk-show host for people who hate talk radio." He is the only radio host in Boston's history to have been on the air for more than 25 years, and his program was consistently the top-rated show in its time slot. David was also a college professor, a movie critic, a frequent television commentator, and the author of a memoir, Life Is Not A Rehearsal. It is a measure of how much he meant to so many, and not only in New England, that his impending death was the biggest story in Boston last week — Page 1 in both daily newspapers, and the lead on every TV broadcast.

IN THE SPRING of 1983, about a year after we'd first met, David Brudnoy took me to lunch. Most of what we spoke about that day, I have long since forgotten. But two things he said still stick in my mind.

One was a comment about wine, a topic about which I knew — and still know — next to nothing. Most white wines are drinkable, Brudnoy told me, but rarely do you encounter a great white wine. The really spectacular wines, he went on, are almost always red — but, alas, most red wines are dreadful.

One was a comment about wine, a topic about which I knew — and still know — next to nothing. Most white wines are drinkable, Brudnoy told me, but rarely do you encounter a great white wine. The really spectacular wines, he went on, are almost always red — but, alas, most red wines are dreadful.

The other remark was about the storm then enveloping Massachusetts congressman Gerry Studds. It had come out that 10 years earlier, the Cape Cod Democrat had been involved in a sexual relationship with a 17-year-old page, and Brudnoy thought the scandal coverage overblown and unfair. This uproar is ridiculous, he snorted. The whole thing was consensual. Nobody got hurt.

Those two remarks weren't a bad preview of much that I would learn about Brudnoy in the years that followed. He was a bon vivant who'd been everywhere, seen everything, and learned to enjoy what was enjoyable in this world. He was also a deeply sympathetic man, tolerant of human weakness and quick to put fairness and friendship before ideology.

Not that ideology didn't matter — it did, greatly. A spirited libertarian conservative, Brudnoy was for many years a contributor to William F. Buckley's National Review, and his acclaimed radio talk show was an important stronghold of the right in a Boston media landscape that tilts precariously to the left. He was a merciless scourge of Bill Clinton, a great booster of conservative authors, and an energetic popper of liberal balloons. Yes, ideology mattered.

But friendship mattered more. And what a talent he had for it! Brudnoy's pals were legion — young and old, white and black, gay and straight, Republican and Democrat. I don't know how I came to deserve membership in that fraternity, but I know I didn't earn it for my politics. There was no philosophical litmus test for his affection. He sharply disagreed with Ted Kennedy on many issues, for example. But he cherished the personal warmth Kennedy had shown him — something he must have mentioned to me half a dozen times.

Brudnoy's homosexuality and religious disbelief fed some of our longest-running disagreements. The last time I was on his radio program, we spent an hour debating same-sex marriage — a cause he fervently supported and I just as fervently opposed.

But his gayness and agnosticism never put the least dent in our friendship. At my wedding in 1996, still frail after his near-death AIDS experience two years earlier, he didn't join in the dancing — which, in the Orthodox Jewish tradition, wasn't mixed. With mock sternness, I waggled a finger at him and ordered him onto the dance floor. "David, don't you realize we arranged this whole thing just so you could dance with other men in public and not draw any attention?" He roared with delight, and told me he was touched by such solicitude.

So many things delighted him, not least of which was his own sense of humor. In 2001 I wrote a column marking Brudnoy's 25th anniversary as a Boston talk show host, and he merrily shared it with his e-mail list.

"So Jeff couldn't think of anything nice to say about me?" the covering message read. "After all I've done for him — officiated at his wedding, circumcised Caleb, took him to his first all-nude gay revival, taught him Tokugawa-era classical Japanese haiku, washed his car every Saturday, took him shopping in Milan for Gucci suits, got him into Skull and Bones — and still he can't say a kind word about me. Jeez!"

"So Jeff couldn't think of anything nice to say about me?" the covering message read. "After all I've done for him — officiated at his wedding, circumcised Caleb, took him to his first all-nude gay revival, taught him Tokugawa-era classical Japanese haiku, washed his car every Saturday, took him shopping in Milan for Gucci suits, got him into Skull and Bones — and still he can't say a kind word about me. Jeez!"

Actually, the Milan reference was accurate. We really did travel there some years ago, and spent a week exploring northern Italy by car. One day, driving our rented Fiat south from Bergamo, we talked at length about religion — in particular, about the afterlife that he doubted was real.

"Just wait," I told him. "One of these days you'll find out it's as real as Milan. And what will you do then?"

That day came far sooner than any of us wanted, but there can't be much doubt about what David Brudnoy is doing now. He is making friends, stimulating conversation, spreading cheer — and doing it all with the gallantry and grace that none of us who knew him is ever going to forget.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.