FIFTY YEARS AGO this week, the Nazis came for my father's family.

The Jakubovics -- there were seven of them in the house -- were awakened before dawn when the SS pounded on their window. Like the other Jews in Legenye, a village on the Czechoslovak-Hungarian border, they were ordered to gather their belongings and prepare to leave at once.

Thirty minutes later they were put on horse-drawn wagons and carted out of Legenye. In the nearest large Hungarian town, a place called Sátoraljaújhely, Jews from all over the region were being herded into a ghetto. The walls were still going up around it as the Jakubovic family arrived.

It was the day after Passover, the ancient Jewish festival celebrating freedom and redemption.

For several weeks the ghetto grew increasingly crowded as more and more Jews were brought in. Then it began to empty, as Jews were taken out.

About 3,000 at a time, they were marched to the train station. The waiting boxcars were filled with families. The doors were chained and locked. There were no seats inside, no windows, no water. The only toilet was a bucket on the floor.

For three days, the train moved -- three days of suffocation, thirst, and filth. When it stopped, David and Leah Jakubovic and their five youngest children, ages 21 to 8 -- Franceska, Markus, Zoltan, Yrvin, and Alice -- were in Auschwitz.

* * *

A few years ago, I decided to chart a family tree.

I unrolled a great length of blank wrapping paper and began with my father's four grandparents, the Weisses and the Jakubovics, writing their names in the center. Those two couples had a total of 12 children, most of them born between 1880 and 1910. I was able to track down the names of 11 -- two of them being David Jakubovic and Leah Weiss, who married each other -- and inscribed them on the sheet.

I learned the names of spouses and filled them in. Then the names of their children, and their children's spouses, and their children. I traced the genealogy as best as I could through five generations, handwriting names and dates on my big piece of wrapping paper.

It was more paper than I needed. This family tree has stumps where branches ought to be. It gets narrower, not wider, as it grows. One line after another stops abruptly, and all with a similar date notation.

Alexander Weiss, wife Kati, son Tomasz -- d. 1942.

Regina Jakubovic, husband Herschel, five daughters -- d. 1944.

Gizella Weiss, husband surnamed Kraus -- d. 1944.

Freida Weiss, sons Robert, Laszlo, Mihaly -- d. 1944.

Leopold Weiss, wife Yolana, four children -- d. 1942.

I have no faces to put to these names, no stories to tell about them, no remarks to attribute to them, no heirlooms to connect to them. All I know is that they were my father's aunts, uncles, and cousins, and like two out of every three Jews alive in Europe in 1938, they were dead before 1946.

If I lose my piece of paper, there will be nothing to prove they ever existed.

* * *

This is how my father, who with rare exceptions speaks about the Holocaust only when he is asked, remembers his first day in Auschwitz:

"We arrived in Birkenau" -- part of the Auschwitz complex -- "on Sunday morning. It was still dark, so it must have been before 5 o'clock. All of a sudden the train stops. The doors open. People started shouting and dogs were barking. There were guards yelling 'Raus! Raus!' " -- 'Out! Out!'

"I remember going up the platform. We had to line up, men and women separately, and go in front of Mengele. He had a little crop in his hands and was waving, left, right, left, right. There were two or three other guys, and they were pushing you, whichever way he pointed with his crop.

"So my parents had to go to the right. Also my youngest brother and sister; they were not much more than babies, small children. What it meant -- left, right -- I didn't know. You just went where you were pushed.

"I went in the other direction. I tried to stay together with my brother Zoli. We had to get undressed, and they gave us the uniforms, and tattooed us. And that was it. But within a few hours Zoli and I were separated, and that was the last I ever heard of him.

"I guess they killed off my family that day, but I didn't know it until later."

* * *

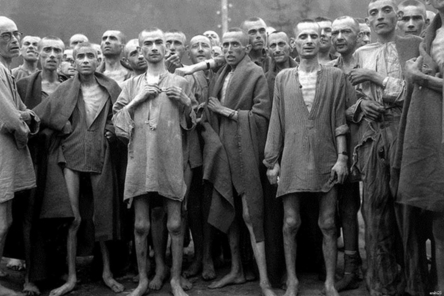

On his first day in the camp, Markus Jakubovic lost his parents and four siblings. He would survive three more concentration camps before liberation in May 1945. By the end he was disease-ridden, emaciated from starvation, and close to death. He still remembers the crematoria chimneys belching smoke day and night and the pits filled with corpses.

He endured a forced march from Poland into Austria, when the Nazis shot on the spot anyone who faltered or paused to rest. He saw Jews hanged when they were caught trying to escape, their bodies left to twist on the rope all day. He used to grab and swallow insects when he saw them on the ground, so intense was his hunger.

But my father is shy about telling his story.

"I feel I had it not so bad as some of the others who suffered in the camps," he says. "I did not go through hell like the others did. You hear about infamous Auschwitz, the horrible stories. I did not have any horrible stories."

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter